What Is audio mastering?

Mastering is the final stage of audio production—the process of putting the finishing touches on a song by enhancing the overall sound, creating consistency across the album, and preparing it for distribution.

Basics of Audio Mastering

Learn the basics of audio mastering with answers to some of the most frequently-asked questions.

Dive into the Are You Listening? mastering series

Learn about the art and science of mastering with professional mastering engineer Jonathan Wyner.

What does mastering a song mean?

Mastering a song involves taking a mix and putting the final touches on it by elevating certain sonic characteristics. This can involve aspects like adjusting levels, applying stereo enhancement, and monitoring for clicks and pops–anything that could distract the listener from the music. The end result is a polished, clean sound that is optimized for consistent playback across different formats and systems.

Is mastering necessary?

Mastering makes the sound cohesive across the record and prepares the music for different distribution formats, such as Vinyl, MP3/AAC, streaming services such as Spotify, and broadcast. In today’s world, mastering is necessary to create that “finished” sound that you hear everyday in everything from television commercials to radio and streaming.

What’s the difference between mixing and mastering?

Mixing happens at the start of post-production, when a mixing engineer sculpts and balances the separate tracks in a session to sound cohesive when played together. Mix engineers reduce imbalances between instruments by adjusting balance and color, tighten rhythmic patterns, and emphasize important song elements with tools like EQ, compression, panning, and reverb.

A mastering engineer then listens to the whole piece as a stereo mixdown. They’re thinking about the finished product and if there’s something they might need to do to improve the sound. This involves correcting and enhancing aspects of the mix including level and tone with tools like

Ozone Advanced

NEW: Master Your Music with Ozone 12

Introducing Ozone 12, the industry's most advanced mastering suite. Unlock the impossible with this complete suite of 20 pro modules, including 3 brand-new, best-in-class additions. Plus, make Master Assistant your own with a new customized flow, and more. With intelligent tech that guides, not decides, you're always in control.

What does a mastered song sound like?

Listen to a few audio examples mastered with plug-ins from

Music Production Suite 7

Hip-hop: “SUMMERTIME” by Antique Naked Soul before/after

EDM: “Shiver (remix)” by Sarah Blackner before/after

Loudness might be the most prominent indicator that the track has been mastered, but consider other elements that your ear is hearing. Are some instruments brighter? Do the levels sound more polished? Does the music feel more cohesive? These are all things to consider when mastering a song.

Start mastering with a free demo of Ozone.

The history of mastering

The earliest forms of mainstream recording technology did not require the recording, mixing, and mastering processes to be separate disciplines.

Rather, the recording was cut directly to a wax disc via a stylus connected to a diaphragm, which was in turn driven by an acoustic horn through which the sound was captured. These wax discs were then used to make stampers, which themselves were used to press shellac-composite 78 rpm discs.

The introduction of the 331/2 rpm long play (LP) vinyl record in 1948, and the 45 rpm in 1949 contributed to a change over time in the record making process. Recordings were being made to tape and engineers were tasked with preparing a master disc from the tape recording. When cutting master discs, these engineers now had to watch for and reduce loud transient peaks present in the tape recording. The energy of these peaks could potentially burn out the disc cutter head or cause the stylus to pop out of the groove when the record was playing.

In order to detect and reduce these peaks, dynamics processing tools such as compressors and limiters were introduced. This was the first time sonic adjustments began to impact the audio after the recording and mixing processes. The need to monitor these tools and adjust the settings for an optimum playback experience without compromising the sound quality was the earliest form of mastering.

The introduction of the standardized RIAA curve meant that equalization (EQ) became part of the mastering discussion. Intended to allow records to be cut with narrower, tighter grooves (and thus, a longer playing time), one side effect of this curve was that the pre-emphasis curve applied to the recording could enhance high-frequency transient peaks, and the de-emphasis applied upon playback could cause a boost in low-frequency energy that would cause the stylus to pop out of the groove.

Slowly but surely, the necessity of these tools to ensure a positive consumer experience meant that the skills of those who could utilize them effectively became highly prized. Some engineers (notably Doug Sax, Bob Ludwig, Bob Katz, Bernie Grundman, and others) began to focus exclusively not just on the practicality of these tools, but also ways in which they could be used to further enhance the listening experience.

Now, many mastering engineers use plug-ins included in the

Music Production Suite 7

How to Master Audio

While there are many ways to master audio, these are basic steps and techniques used to accomplish a finished master.

Pre-Mastering Prep

Double-check that you have the correct files

Double check that the mixes you’re mastering are in lossless full-resolution quality—WAV format in the mix session’s native sample rate with the bit depth at least 24-bit or 32-bit float is recommended. Avoid mastering mixes in lossy formats such as MP3s at any cost. It also won’t hurt to check that the mixes are in stereo as opposed to mono (it happens!).

Request for metadata (artist name, song/album name, track listing)

Having the metadata right at the beginning of the mastering stage helps maintain a smooth-flowing mastering session, especially when mastering a full album. Knowing the track listing beforehand is crucial in ensuring a cohesive musical flow from beginning to end. Proper metadata also ensures accurate documentation of the files/session on your end, thus avoiding any potential problems with archiving.

Optimize your mastering workstation with proper calibration

Calibrating your speakers to a fixed monitoring gain allows your ears to develop an internalized reference for loudness and tonal balance. Equally important, however, is the proper gain-staging of your signal chain—making sure each point of amplification is calibrated to ensure an optimal signal-to-noise ratio and minimal distortion. It could be as simple of a habit as feeding a test tone before every session (1 kHz sine wave) through your analog outboard gear to ensure that the left and right channels are balanced.

Listen before you start mastering

Begin any mastering session by listening to the music from beginning to end at the full, optimal level. This might seem like a mundane task but it’s especially important. This provides you with a head start on strategizing your mastering gameplay. You get a more thorough picture of the musical content from the intro all the way to the explosive final chorus and outro, along with any unexpected changes in sections such as the bridge. Knowing all these details beforehand ultimately makes you more productive with your mastering decisions. Less time wasted course-correcting as you adjust to unexpected changes along the way.

Step 1: Establishing the “Aesthetic” and Sound of the Song

When you’re engaged in mastering, you’re trying to make final decisions about whether to change something–whether it needs to sound different in one way or another. The goal is to make a song “sing,” making it sound as good as possible. Does the mix sound too bright? Does it have too much low end? This first step can involve adjusting levels and examining the tonal balance of the mix, as well as repairing the audio and removing unwanted clicks, pops, or noise that was leftover from the stereo mixdown. This step can also involve listening to reference tracks to get an idea of the sound you and your artist are looking for, and using tools like

Tonal Balance Control 2

Ozone modules

Specific Processors Used in Mastering

Digital Signal Processors (DSP) electronically analyze, modify, or synthesize signals, such as sound. For example, the entire Ozone mastering plug-in can be viewed as a single DSP processor, while individual

Ozone Advanced

Compressors, Limiters, and Expanders

Compressors, limiters, and expanders are used to adjust the dynamics of a mix.

Equalizers

Equalizers are used to shape the tonal balance by boosting or cutting specific ranges of frequencies.

Stereo Imaging

Stereo imaging can adjust the perceived width and image of the sound field.

Harmonic Exciters

Harmonic exciters can add an edge or “sparkle” to the mix. Adding combinations of odd or even harmonics to the frequency can create a sense of “energy” in the mix.

Limiters/Maximizers

Limiters/Maximizers limit peaks to prevent clipping as the user increases the overall level of the audio.

Metering

Metering is any visual aid that helps mastering engineers measure various aspects of their mixes, helping them make better decisions about frequency content, stereo spread, levels, and dynamic range.

Dither

Dither is used in cases when it is necessary to convert higher word-length recordings (e.g. 24 or 32 bit) to lower bit depths (e.g. 16 bit for CD) while maintaining dynamic range and minimizing quantization distortion.

With all these types of effects, you might wonder where to start. First off, remember, just because you have all these processors doesn’t require that you use them all. Only use as many as you need. In truth, there really isn’t any single “correct” order for effects when mastering, and you should feel free to experiment. Here’s an example of one step-by-step process.

Make Mastering Easier with Assistive Audio Technology

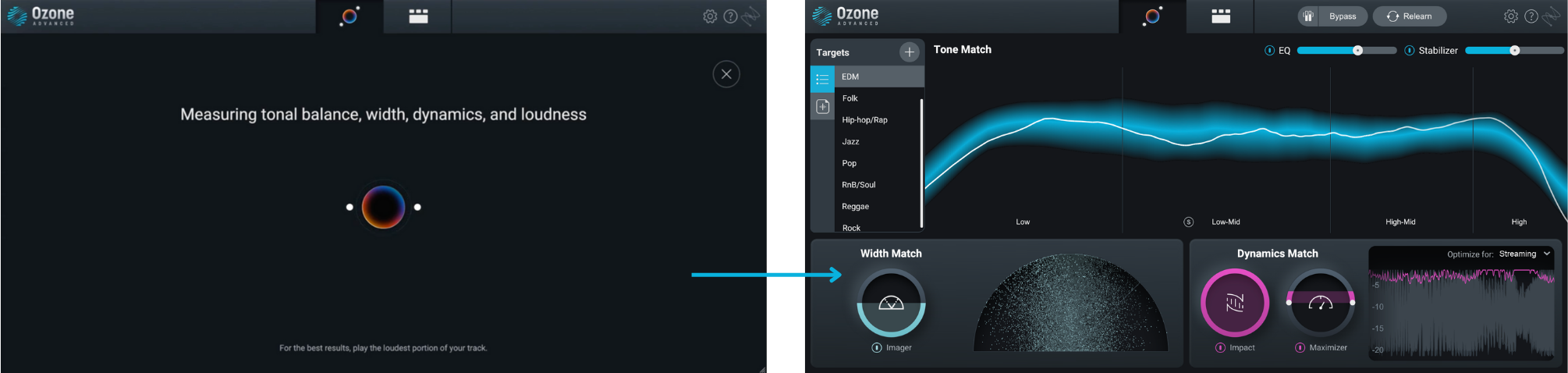

One way to get to a great starting point in your mix with these processors is taking advantage of assistive audio technology used in mastering plug-ins like iZotope

Ozone Advanced

Another example of assistive audio technology that can make quality control in mastering easier is in RX’s Repair Assistant that can easily detect noise, clipping, clicks, hum and more.

Step 2: Creating Consistency Across an Album

How do the individual tracks of an album sound when they’re played in succession? Having a consistent sound, making sure the levels are matched, achieving the same “character” from one song to the next and ensuring even playback are all means of creating consistency across an album.

While some of this is achieved in step one, it’s important to carve out a step for evaluating how individual tracks sound in relation to each other when played in succession. This is not a “make one preset, set it, and forget it,” situation where you have the exact same treatment on all your tracks. The main goal is for the listener to feel like they’re in the same “space” throughout the entire listening experience, and never touch the volume knob when moving from song-to-song, which will most likely mean using different settings, even different processors for different tracks.

Once you’ve nailed and printed the final sound across your tracks, avoid neglecting the tops and tails of your masters. Apply the necessary fade-in and fade-outs that complement the music. For example, refrain from absent-mindedly applying an abrupt fade-out that could detract from the musical ending the artist painstakingly worked hard to create. Similarly, apply the same attention to the silence and spacing between tracks when you’re mastering a full album. Intention is key!

There may also be the rare instance where a noise in the mix suddenly pops out after mastering. Or you might hear a subtle distortion in one spot. You can easily treat these spots without disrupting the sound of the final master with the creative use of RX as mentioned above.

Step 3: Client Feedback

We’re not at the finish line just yet! One can safely say the mastering’s complete only after receiving the artist/client’s approval. Client feedback and revisions are an equally important part of the process and shouldn’t be an afterthought. It’s an integral part to understanding the artist’s vision, after all. Encourage your client to be as open with their feedback as possible. Revisions might go through a couple of rounds especially on your first session, but the more you get to know your client’s sound, the more efficient your next sessions go. Mastering is very much a collaborative process.

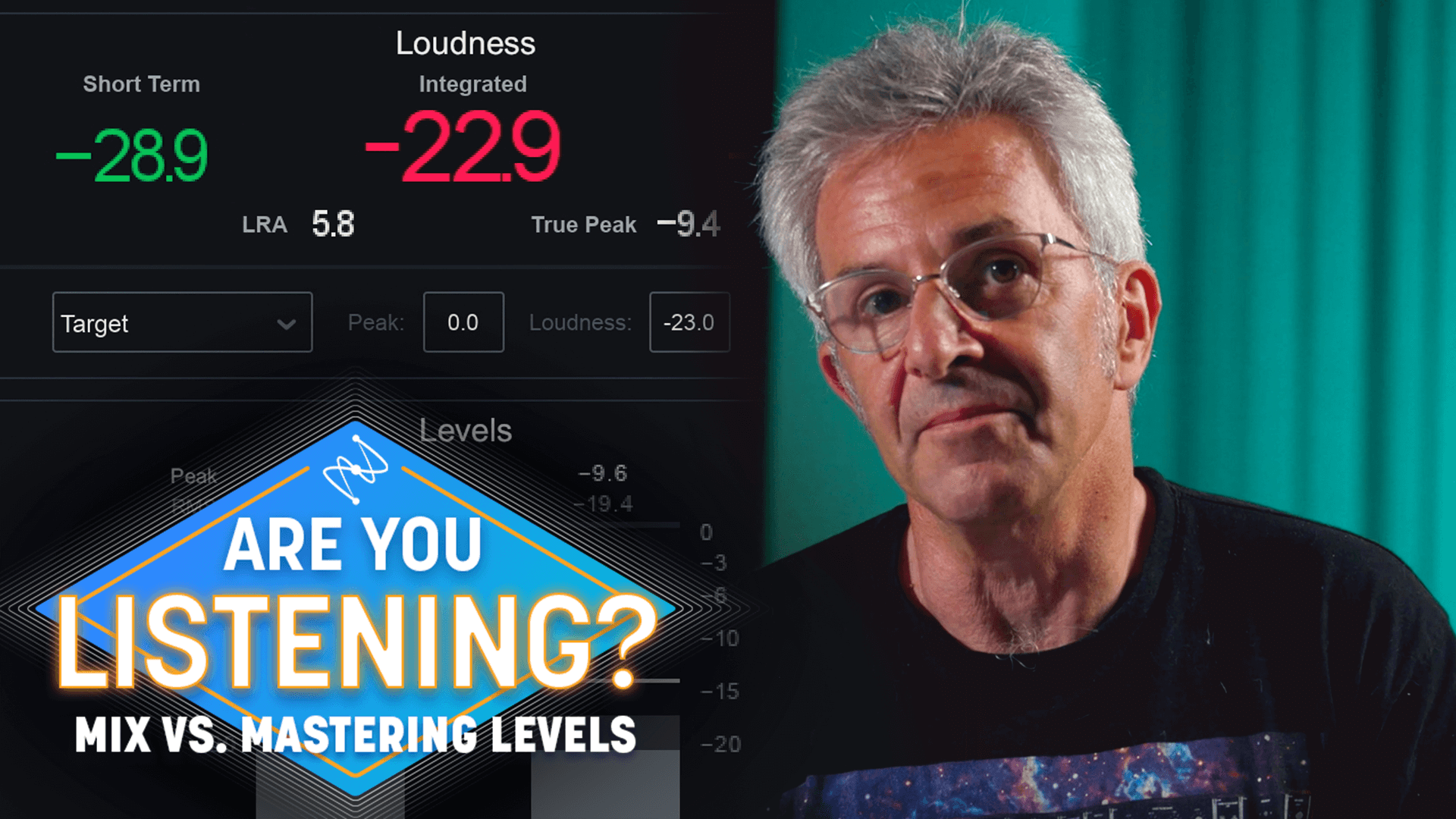

Step 4: Preparing for Distribution

Preparing your tracks for distribution is a crucial step in mastering that results in your listener having the experience that you want them to have. This involves ensuring the levels are set right, making sure there’s nothing wrong with the audio, and making sure that the audio isn’t too dark or too bright compared to the rest of the audio tracks in the world. The delivery format of the song or sequence of songs for download, manufacturing, and/or duplication/replication is also an important consideration. This varies depending on whether you’re exporting with vinyl, CD, for broadcast, or for streaming. For web-centered distribution, you might need to adjust the levels to prepare for conversion to AAC, MP3, or hi-resolution files and include the required metadata.

Learn More About Audio Mastering

Below are a series of helpful resources to get you started on your audio mastering journey.

Learn from the pro in Are You Listening?

Professional mastering engineer and iZotope Director of Education Jonathan Wyner teaches the art and science of mastering in the Are You Listening? mastering video series.

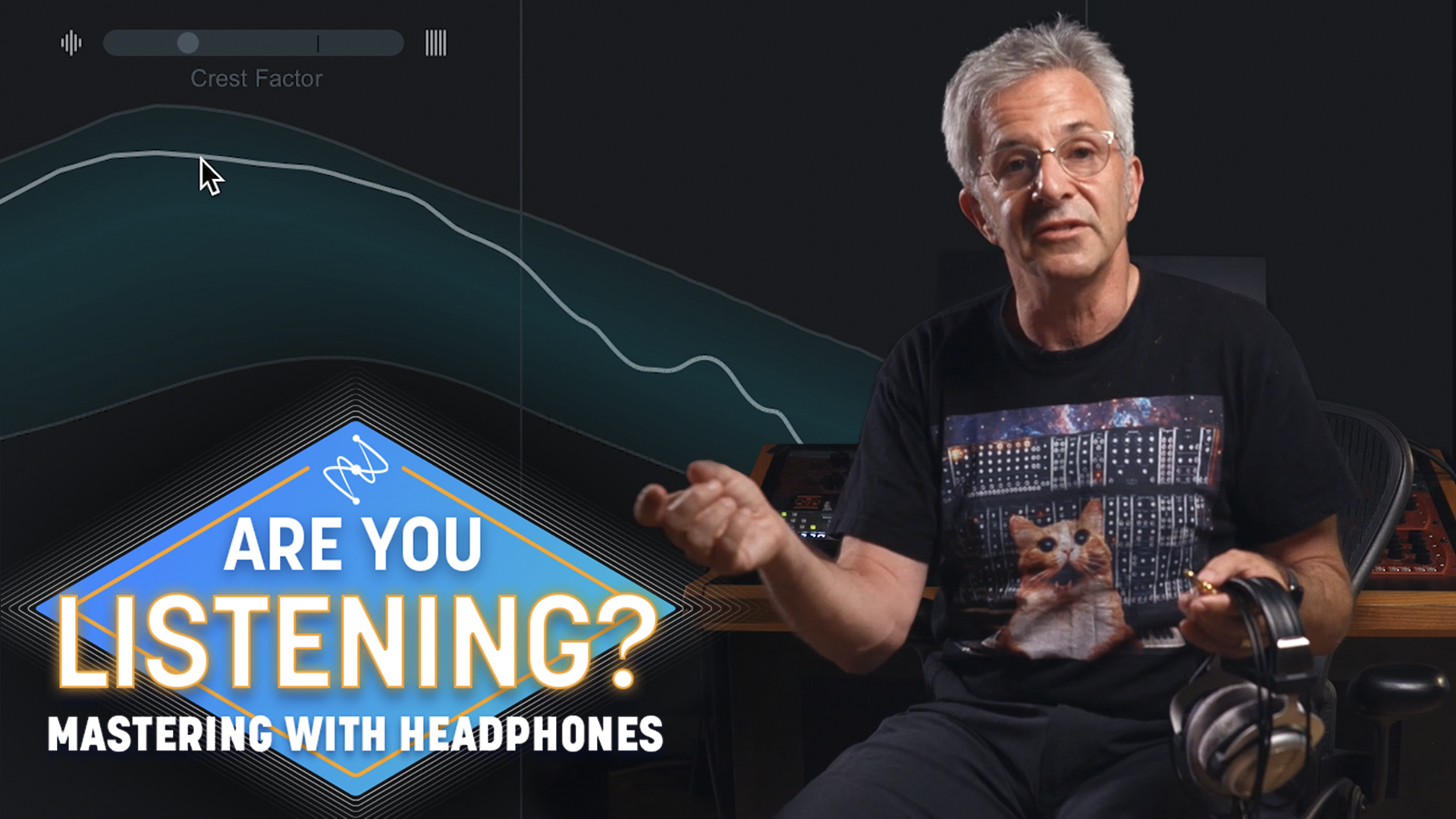

Mastering with headphones

Excitation in mastering

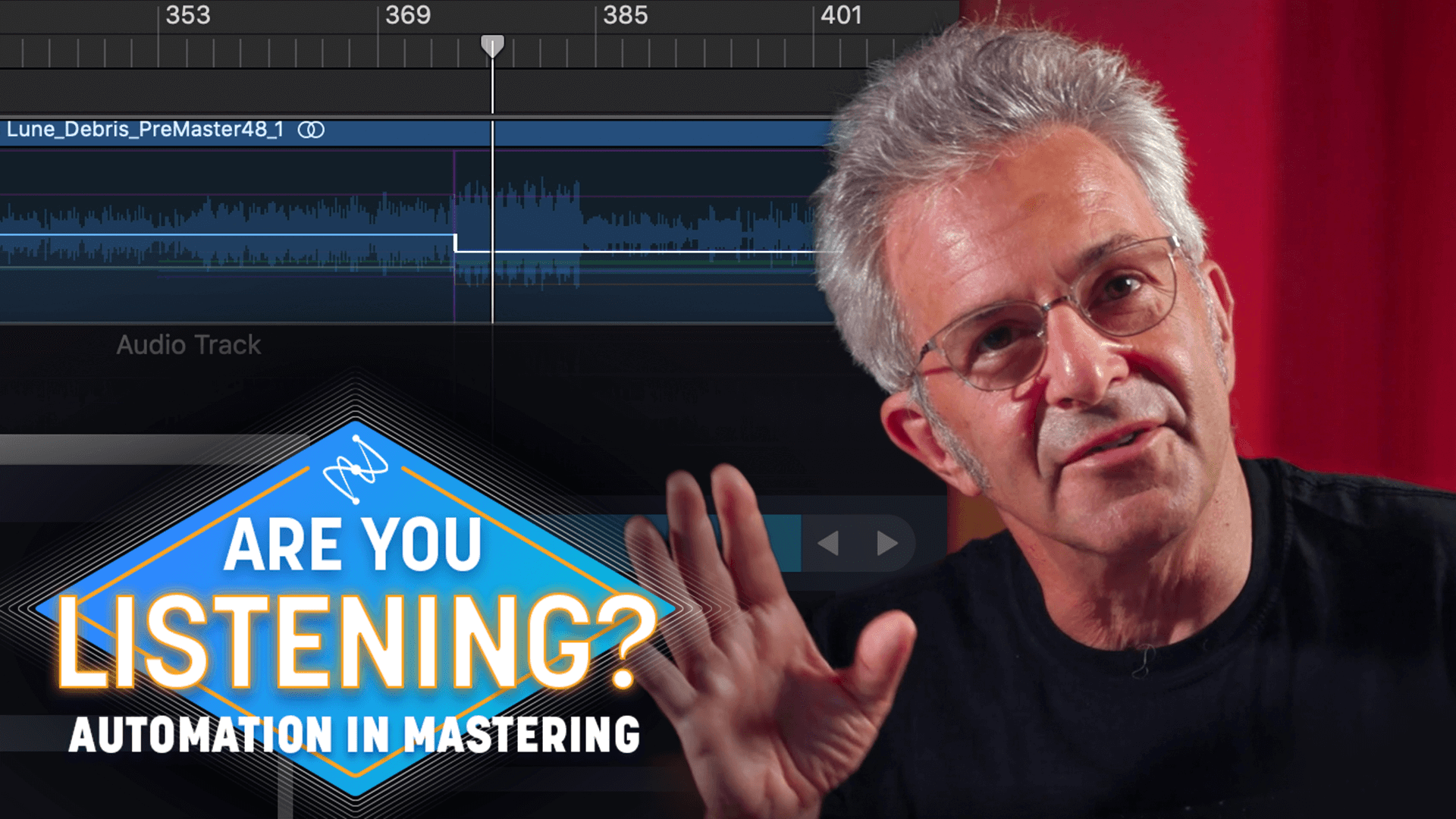

Automation in mastering

Mix vs. mastering levels

Learn how to become a mastering engineer with Jett Galindo

As a

iZotope Music Production Suite Pro: Monthly