5 mixing trends defining 2025 (and how you can use them too)

Discover the five mixing trends defining 2025, from the new role of AI in your workflow to why vocals dominate the midrange.

Every year brings new “game-changing” technologies and sonic fashions to the world of music production, and 2025 is no different. But while press releases might trumpet a shiny future of AI-automated mixes and immersive formats, the real story on the ground is often subtler – and more human.

What follows are five mixing trends that define sonics in 2025. They range from the way vocals now dominate the midrange, to how nostalgia for the early 2000s reshapes indie rock, to the ongoing non-debate over loudness, AI, and immersive audio.

Try out some of the trends from this article using a free trial of

iZotope Music Production Suite Pro: Monthly

1. Don't fear the AI: it's a tool, not a tyrant

AI is here, and it’s all the rage – and by rage, I really mean both senses of the word. Among forums, listservs, groups, and private conversations, there’s constant talk about whether AI is going to take our jobs.

Indeed, the tools seem to be pitched at everyone: AI is supposed to make mixing engineers work faster, but it’s also supposed to supplant mixing engineers for people who can’t afford them. Same goes for mastering: mastering engineers have to compete with more AI stereo bus processors than ever before. Prompt-based tech is being implemented into plugins now, and ChatGPT can supposedly give you mix notes. Some technology can apparently create whole songs for you.

So am I worried? Maybe, but not because of AI.

For one thing, the tech isn’t quite there. Aside from iZotope tools – which are correctly positioned as helpers and starting points rather than usurpers and supplanters – the quality is lacking. AI isn’t giving you anything that a professional wouldn’t have to fix to make palatable. Sure, neural nets are making the job of noise reduction much easier, but AI can’t seem to EQ one track in relation to another.

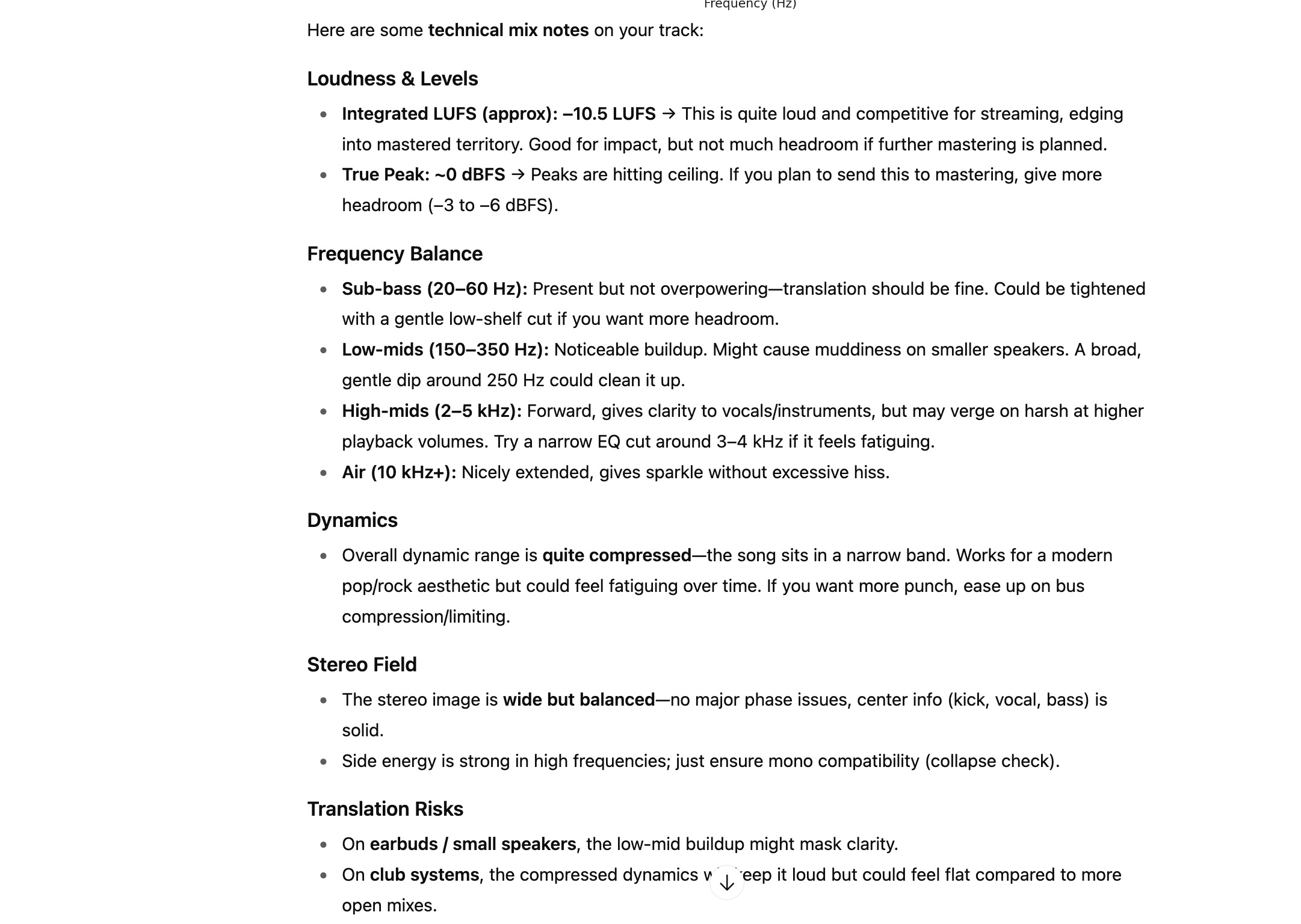

As for mix critiques? Here’s what ChatGPT says about a tune I put into its clutches:

ChatGPT mix notes

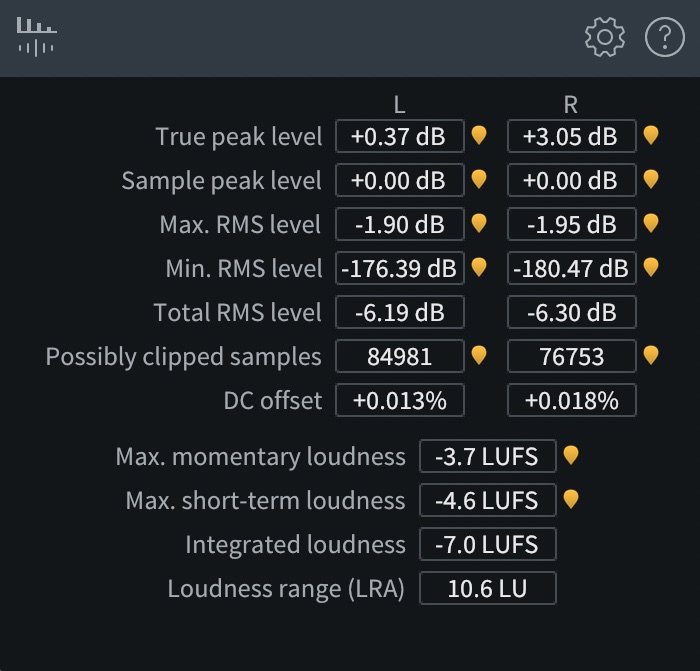

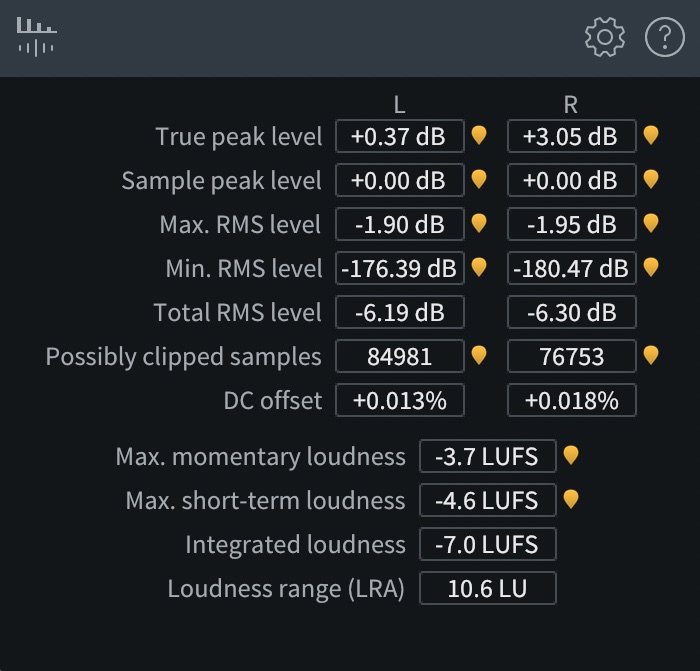

What’s the problem here? Well, the song is “Golden,” currently the number one hit on the Billboard Hot 100 and Spotify’s global charts at the time of writing. I might also mention that it’s also lying: the integrated LUFS measurement isn’t -10.5. It’s -7 LUFS.

"Golden" waveform statistics

In day to day life, people seem to be able to tell the difference between something generated by humans and generated by AIs. The fake vocals aren’t fooling the youngins I know, and in my dealings with clients, they want to avoid AI at all costs. There seems to be a real gut-level negative reaction to this stuff.

So why would I be worried?

It sure feels like AI is positioned as a big bogeyman to the livelihood of people in the arts – but I’d argue that’s more of a distraction from the real, human-powered challenges. The fact is, economic shifts – from inflation to streaming revenue models – have made it harder for musicians to pay what a professional mix is truly worth.

The result isn't a race against robots, but a heightened demand for efficiency and value. This environment is where assistive mixing tools become indispensable, allowing us to deliver high-quality results faster, making professional mixing more attainable for clients navigating a tight economy.

AI in mixing: the practical takeaway

I said before that iZotope is one of the few companies doing AI right, and I don’t mean this in terms of blind marketing. The assistive technology in Ozone, Neutron, Neoverb, and Nectar are fantastic at getting you starting results, using AI-tech like machine learning to get you closer to your intended result.

To give you an example of what I’m talking about, let’s take this static mix of an acoustic tune for Pete Mancini, which features absolutely no EQ on the instruments.

Now, let’s run it through Ozone for a stereo bus starting point, using the acoustic song “Your Move” by Ian Ball as a reference in Ozone.

What we’ve got now is a good starting point – and I am free to use as much of it as I want. You can see how I began to tweak it on the macro level; I am free to tweak further, so that it becomes something I choose to mix into.

2. The 2000s are the new indie reference

Onto something arguably less depressing:

If you’ve felt like the clock has rewound to the early aughts, you’re not imagining it. The nostalgia cycle runs on a 20–25 year delay, which puts us right back in the golden age of Hipster chic. This is quite apparent in the music I’m hearing and the requests I’m receiving.

In indie and alt sessions, The Strokes are a reference everyone is telling me to utilize. That sharp, garage-rock minimalism – thinner mixes, guitars clashing, vocals smeared in grit – has reemerged as a dominant reference.

A personal anecdote: when I sent in my v1 mix to Micah E. Wood for his tune “You, Me, The Reign”, he had one prominent note. He wanted distorted 2000s vocals, like The Strokes. Here’s where we arrived.

What did I use to get grit on my vocal? Ozone’s Exciter module – with oversampling on:

Vocal Exciter settings in Ozone

If indie clients aren’t chasing The Strokes, they’re going for Mk.gee – a sound awash in lo-fi distortion, midrange verbs, digital artifacts, and Bon Iver. Indeed, you can strike a direct lineage from one band to the other.

For that kind of production, awash in reverb, I’d probably turn to time-based effects with built-in resonance suppression to keep them from getting out of hand. Tools like Cascadia and Aurora come in handy.

Aurora reverb plugin

It’s important to mention that harkening back to the 2000s isn’t a copycat phenomenon, however. What we’re seeing is a melding of an old sound with new and modern tools.

The old guard came upon its sound out of necessity. Today’s tools offer fidelity leagues beyond the 2000s at a fraction of the cost.

Yesterday’s necessity has become today’s texture.

3. Vocals are filling up the midrange like never before

Let’s start this trend off with a listening exercise.

- Take “Golden” and reference it against Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Run Away With Me.”

- Take “Ordinary” and reference it against Imagine Dragons’ “Believer.”

- Take “Back To Friends” and reference it against “Electric Feel” from MGMT.

- Take “Don’t Say You Love Me” and reference it against “Can’t Stop The Feeling” by Justin Timberlake.

Now, don’t just listen to them back to back: filter them through something that focuses your attention on the midrange. For this exercise, I used MetricAB’s midrange isolation feature, which spotlights everything from 800 Hz to 4 kHz:

ADPTR AUDIO Metric AB

This is a crucial band, for everything from iPhone speakers to club systems will tend to reproduce it well; your tune must communicate through this frequency range.

So what trend will you notice, if you engage in this exercise?

The vocals are dominating. And by dominating, I don’t mean they’re simply louder. I’m talking about the tonal relationship between the vocals and the instruments in the midrange: each of the modern tunes somehow gives us less of the instrumental bed in this crucial band, allowing the vocal to soar unencumbered.

In the historical references, you can hear more crack from the drums, more grit from the bass, more presence from the synths, and more growl from guitars in this narrow range. That’s a stark contrast from today’s mixes, which tend to shape these instruments away from the vocals in the high mids.

This isn’t a coincidence. It’s a new style, enabled by the tools we now take for granted: masking analyzers, frequency-selective dynamics, and surgical EQs that let mixers carve space with precision. It’s not all across the board, of course, but it’s noticeable.

iZotope offers tools that help in this regard, of course. Neutron has its Unmask module and Masking Meter.

Neoverb, on the other hand, has intelligent inter-plugin communication to keep one instrument’s reverb out of the way of another.

Neoverb unmasking

These tools help in chiseling instruments away from the vocal.

Of course, global adjustments help in this regard as well: turn off that midrange filter in MetricAB, and you’ll notice other trends that reinforce this midrange phenomenon.

Listen closely to the low-mids, around 300 Hz. In today’s productions, instruments are often scooped out here, giving more room for the vocal’s warmth without letting the mix turn muddy. You can achieve this with any number of EQs, from Ozone to the Amek 200.

Another trick I’m hearing a lot on the charts: dynamic cuts on reverb returns, usually in the side channel around 1 kHz. Sometimes it’s multiband compression, sometimes downward expansion – but the results are the same: When the vocal is in, the reverbs politely duck out of the way.

You can achieve this effect with Kirchhoff’s dynamic EQ, Ozone’s multiband compressor working in M/S mode, or Neutron. If all your reverbs are routed to their own submix, simply slap the processor on that return and tamp the sides down as need be. With a tool like Neutron, you can even duck the side-channel compression to the vocal itself.

4. No one really cares about normalizing or true peaks

This is more of a mastering takeaway, but it informs mixing as well, because loudness really does start with the mix.

Check the charts right now and you’ll see tracks slamming in at -5 or -4 LUFS short-term, with huge intersample peaks baked right into the final product. Again I point you to the number one hit in the country:

"Golden" waveform statistics

We’re hitting true peaks of 3 dB, with tons of clipping. In some cases, this clipping is quite audible. You’re far more likely to hear side effects of such loud productions: distortion, artifacts, and arrangement decisions made specifically to survive loudenation.

Meanwhile, in the sales-funnel economy of YouTube practitioners, creators are backpedaling on their previous loudness predictions. Remember when -14 LUFS was supposed to be the standard? That conversation has aged about as well as heralding Atmos as the next big thing (more on that later). Big voices in the space now admit the end of the loudness wars never really showed up.

Most mastering engineers are pretty sick of talking about loudness too. They just want the record to sound good within the constraints of our era. –7 Lufs integrated? Sure. Higher? Fine. True peaks? Another collective shrug. As long as the work keeps coming.

Do I see a problem with this? Absolutely not. Distortion is just part of the sound now, and sometimes, it sounds fantastic. If the world wants to turn up the music in the face of so much bad news, who am I to complain?

To the extent that normalization changed the sound of mixing, it did so in a way that is designed to confound the weighting inherent in LUFS measurements. Mixing the track so vocals dominate the midrange? It’s not just a trend – it’s free loudness when normalization pulls your track volume down. What about the bass being sculpted to within an inch of its life? Another necessary evil: bass is one of the first things that causes a mix to read louder than it is, resulting in a severe normalization penalty.

The bottom line is, the pop world is delivering mixes that are pinned as loud as ever, and no one’s losing any sleep over it.

What tools can help you achieve this sound, should you be interested in?

Check out the clippers on offer from iZotope and Brainworx for your instrument buses if you’re working in electronic genres. Drums specifically can benefit from clipping on the bus.

Neutron Clipper on the drum bus

And, make use of Ozone on the stereo bus – particularly the bass control module for keeping your low end in check, as well as Ozone’s newest and most raved-about feature: IRC V. This thing has a way of letting you get loud in pop genres without incurring enormously obvious distortions – if you use it well.

5. Immersive audio: a major label requirement, not a listener priority

In my world, immersive audio comes up often – but almost exclusively in post production for film and podcasts.

When it comes to music mixing, it’s a different story. In my circle, and based on surveys of my peers, the only engineers tackling immersive audio mixes are doing so to satisfy the specific demands of major labels. It's viewed, often, as a necessary addition to the service catalog rather than a creative necessity.

As of 2025, it's fair to say that the enthusiasm for immersive audio like Atmos is concentrated at the top tier of the industry. While huge commercial studios invest heavily in rigs, consumer data on actual listening habits remains elusive.

The growth in soundbar sales, for instance, arguably reflects an interest in cinema sound more than a surge in music consumption for the format. And while data once showed high trial rates for binaural Atmos, we're not seeing current public data to confirm sustained growth in streaming numbers.

This is why I see immersive audio as being for the majors, not the masses. It's a new revenue stream for the industry – a way to repackage old catalogs, much like the CD revolution of decades past. And while it’s great that it's creating work, its broader impact on the average music listener and the vast independent music ecosystem is minimal.

The ultimate proof? The world's largest streaming platform, Spotify, remains firmly focused on stereo.

Be informed, not cowed

Taken together, these five trends illustrate a music ecosystem that is both cyclical and disruptive.

So what does this mean for you, sitting in front of your DAW? First, it means the fundamentals matter more than ever: balance, tone, and translation across playback systems are still the difference between a mix that moves people and one that falls flat.

Second, it suggests that learning to navigate these trends without becoming beholden to them is the real skill. Use AI to audition EQ curves or unmask competing frequencies, but don’t rely on it to make decisions. Reference The Strokes or Mk.Gee, but contextualize those textures in your own sonic world. Keep your eye on loudness targets, but don’t let numbers dictate feel.

But remember this above all: mixing in 2025 isn’t about chasing every fad. It’s about understanding where the currents are flowing, then choosing when to ride them, and when to do something different.