1920s to Now: Comparing Tonal Balance in Popular Music

We ran a bunch of songs through the Tonal Balance Control plug-in. This is what we discovered about frequency distribution in mixes from each era of popular music.

Why do the Beatles recordings sound the way they do? What about the classic jazz recordings of Rudy van Gelder in the 1950s? What makes my car’s license plate vibrate like it’s going to fall off when I crank a Dr. Dre production?

There are a number of ways we can quantify the differences and/or similarities between recordings. Audio technology has developed over the years to give us various methods of learning about the sounds we hear. We have meters and visualizations that help us look at spectra, the musical and technical dynamics short and long term, and average level and other qualities to help us describe the sounds. iZotope makes a plug-in called Tonal Balance control that puts a lot of this information into a single visualization, letting the user compare the tonal balance of a song (or songs) with each other or against an idealized shape; this makes it possible to see some of what makes these very different recordings sound so different.

Read why iZotope created the Tonal Balance Control plug-in here.

If I want a particular recording to sound like a Motown recording, I would need to recreate that environment down to the room and gear, not to mention having the ears of Bob Olhsson. Pick any era and any recording medium, technology has always helped shape the sound of the finished product.

The Tonal Balance Control plug-in is incorporated into Ozone 8 and Neutron 2, so now I can compare all kinds of music to better understand what I’m hearing, and adjust my mastering EQ to bring that frequency response curve into alignment with a target source. (My inner geek shouts with glee at the prospect.)

Many engineers have used an RTA (Real Time Analyzer) to check the frequency response curve of their mixes, but this is a new way to approach comparing source to destination. Here’s what Tonal Balance Control does and how you use it.

Note that Tonal Balance Control is normally used to assist in measuring and adjusting the balance of your mix. However, in this case we use it as an analysis tool to learn about what tonal balance looks like on multiple songs throughout the ages.

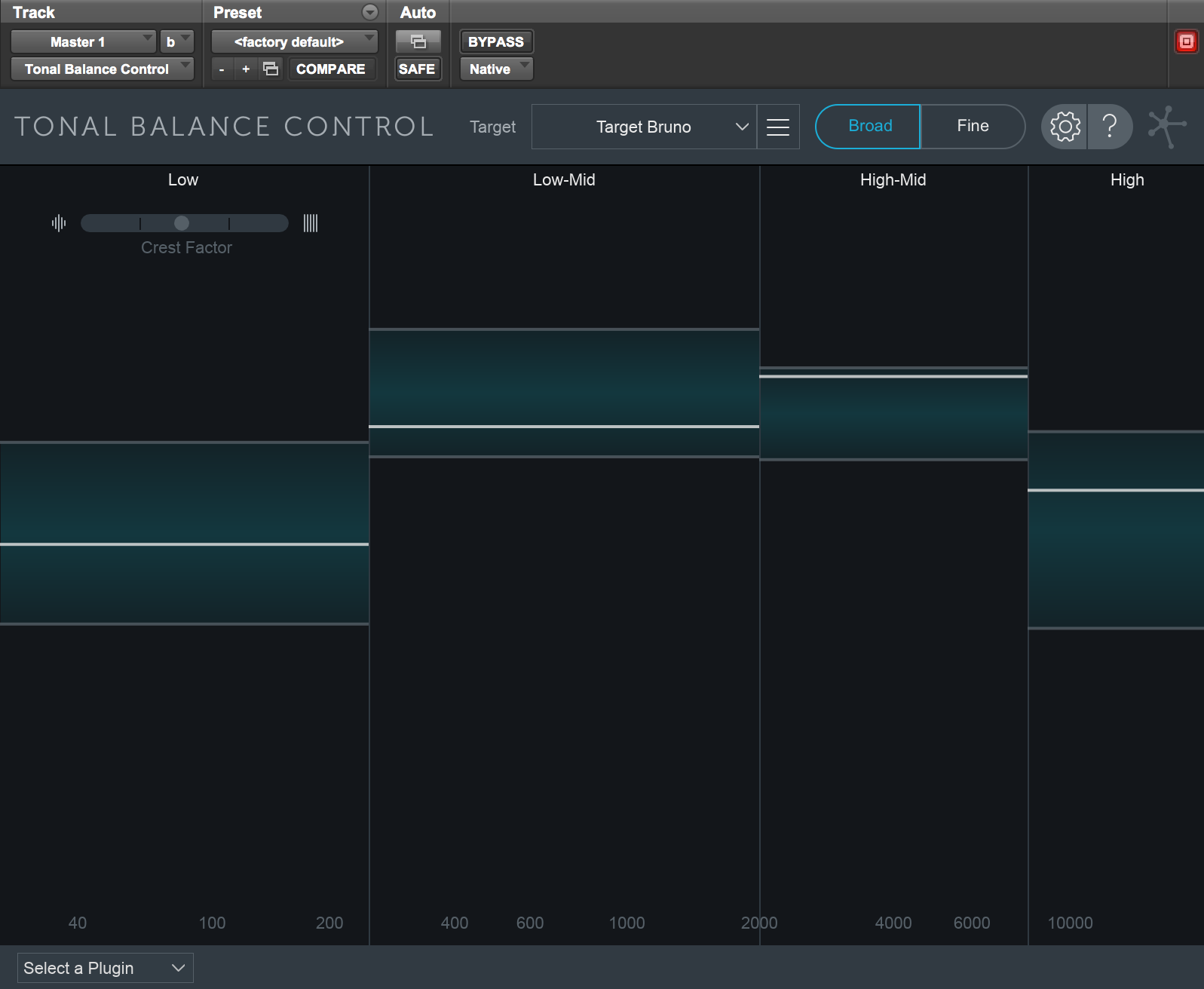

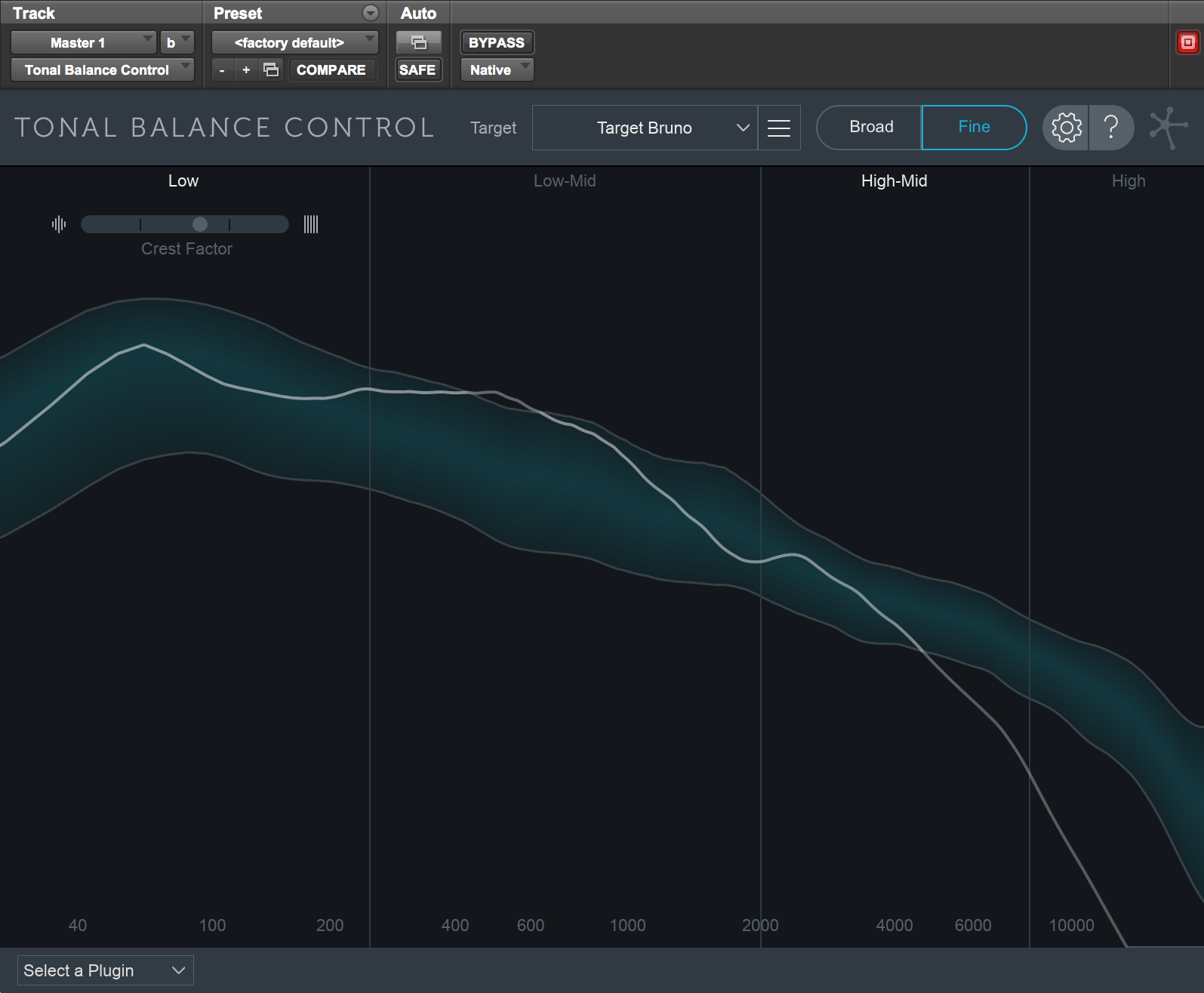

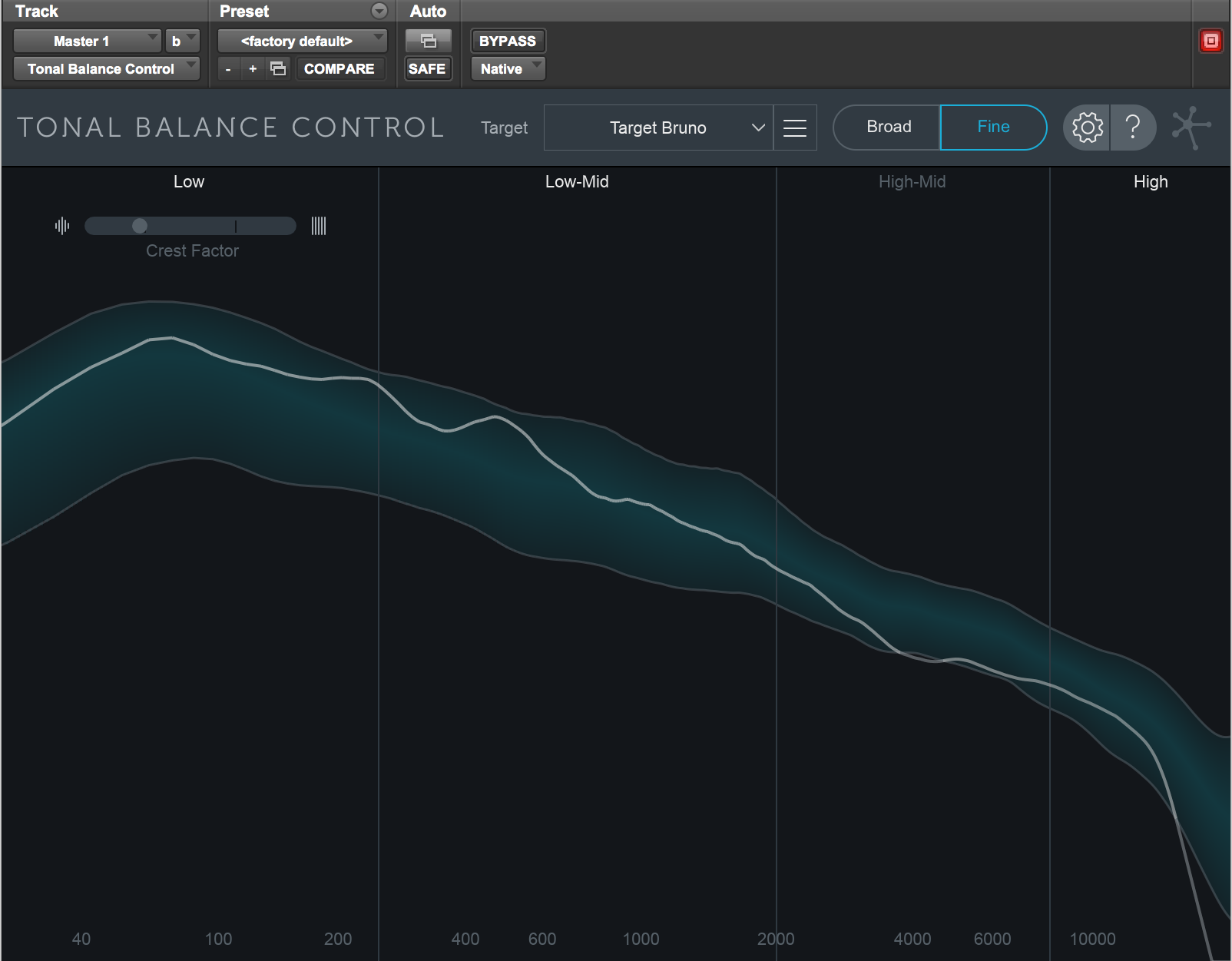

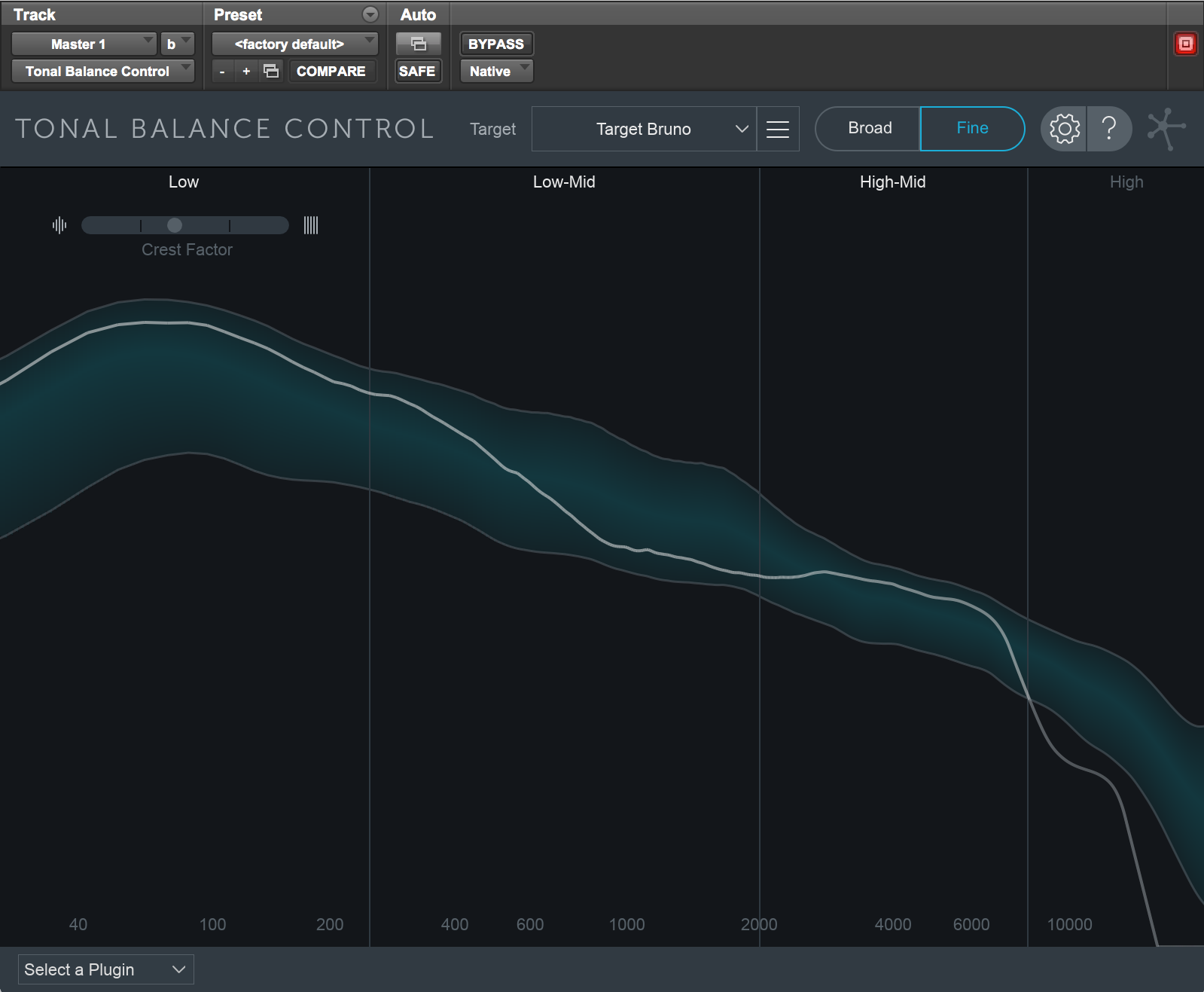

Given that recording technology and production techniques have changed markedly throughout the 20th century, the sound of recordings has changed just as dramatically. For the purposes of this article, as we examine the tonal balance of seminal songs, we’ll use a modern reference for comparison: the 2018 GRAMMY® winner for Best Engineered Non-Classical Recording, Bruno Mars’ "24 Karat Magic." This will be our benchmark for tonal balance.

The screenshot below is a snapshot of the tonal balance from the song “24 Karat Magic” as compared with the Bass Heavy preset from the TBC plug-in. You can see that the Bruno EQ curve (the narrow white line) falls neatly within suggested frequency/amplitude boundaries for Bass Heavy music.

Bruno Mars Reference, "24 Karat Magic"

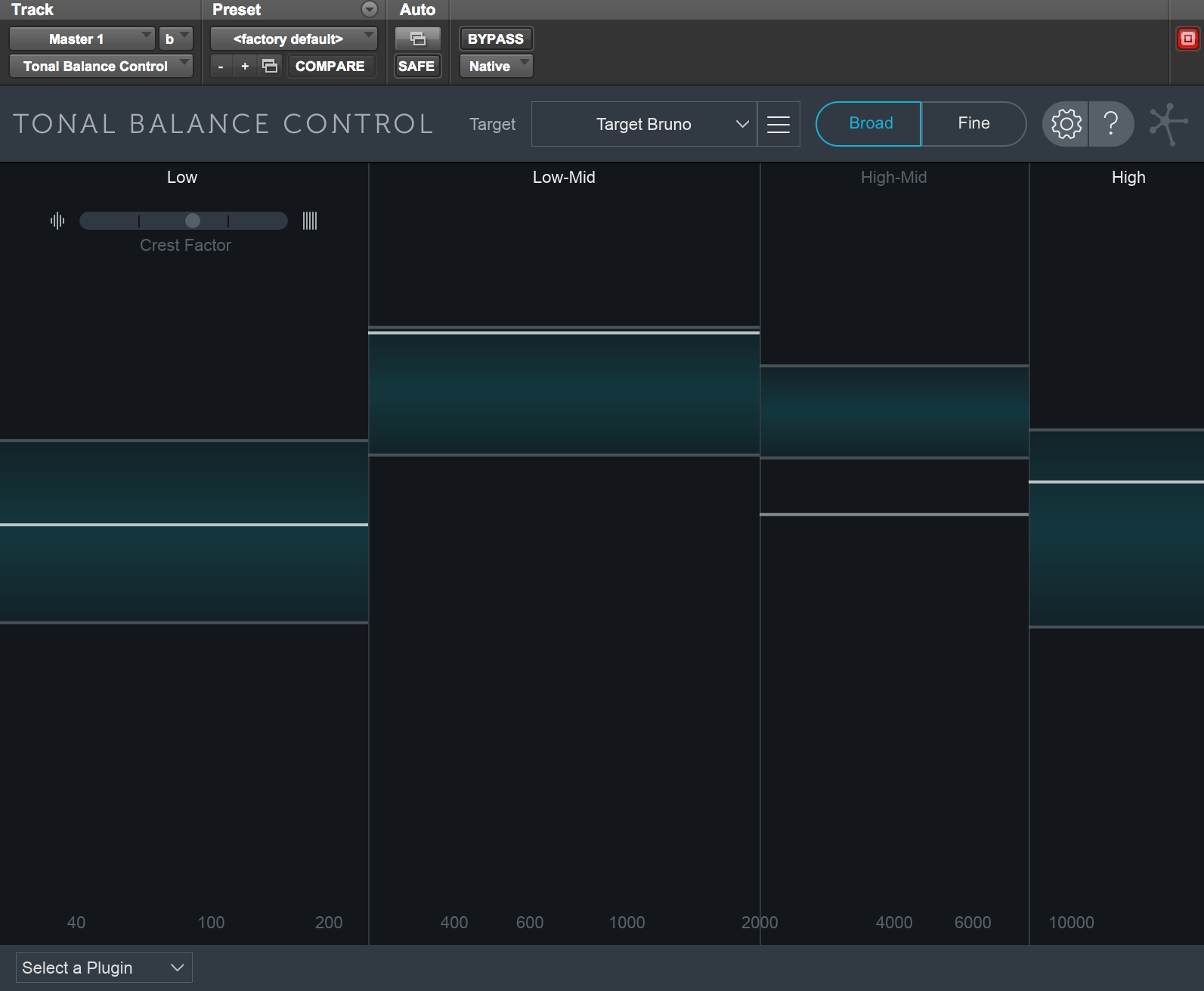

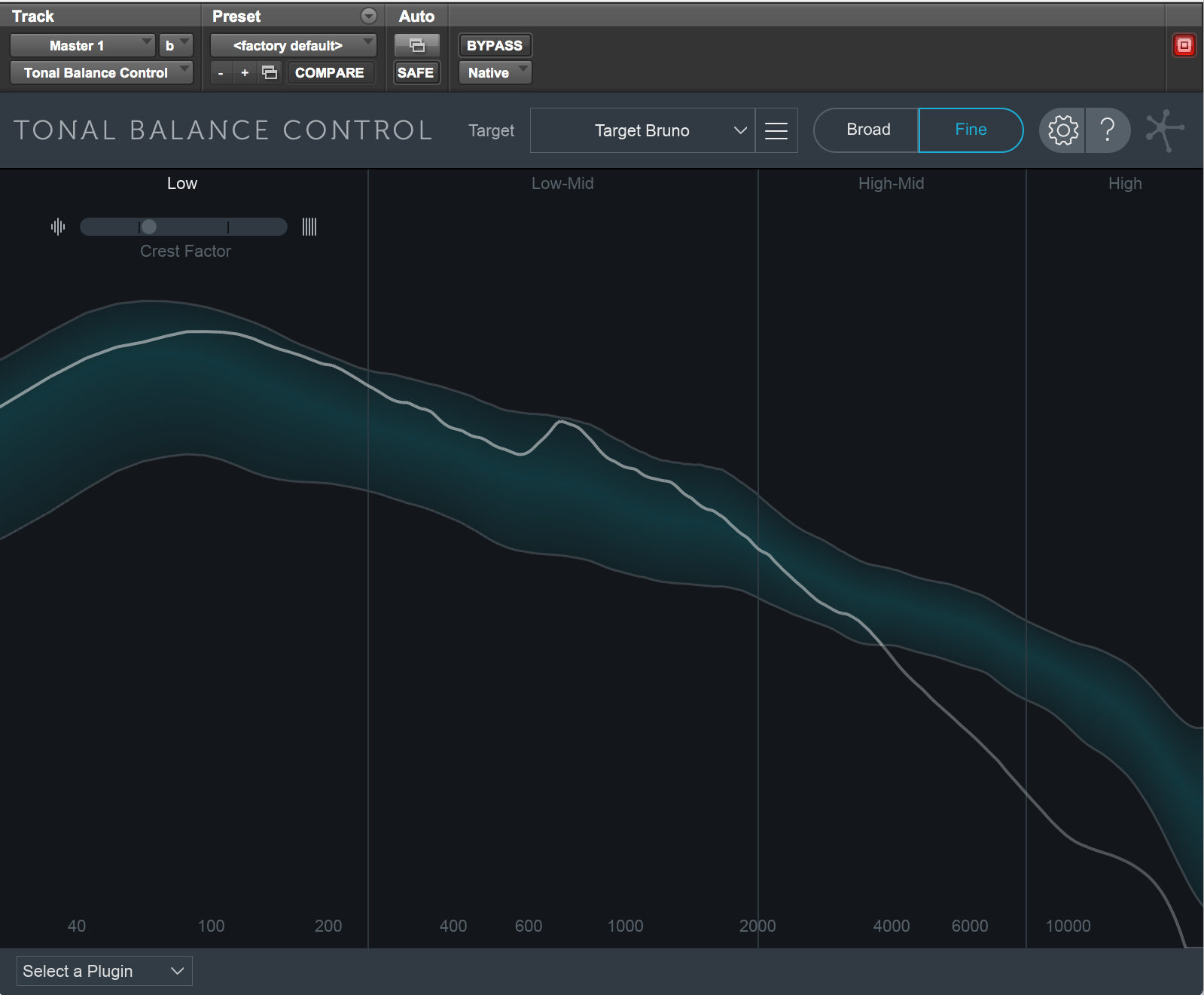

Here’s a simpler way to look at four bands for tonal content, in Broad mode:

Bruno Mars "24 Karat Magic" Reference, Broad Mode

Now for the fun part: after some experimentation and comparisons with recorded music through the ages, this is what I found.

Pre 1920

Before recordings were made and distributed on vinyl and lacquer discs, all recordings were made with an acoustical transcription device, like a Gramophone or an Edison wax cylinder machine (above). The Scots have a special word for the resulting sound quality, which I won’t mention here, but it was the hippest (and only) transcription technology available at the time. Let’s just say it was not the kind of quality we expect from today’s music.

For my first example, I selected a George M. Cohan song, “Over There,” as sung by Nora Bayes, as it seemed exemplary of WW1 recordings in the golden era of 78 RPM 10” lacquer discs. This is a visual comparison of “Over There” (thin white line) to our Target Bruno benchmark:

George M. Cohen, "Over There"

As you can see, there’s lots of midrange, and not much low-end license plate rattling going on. The high end tapers off after about 3 kHz, but the high frequency energy you see on this graph comes from surface noise on the disc. A turntable playing a 78 RPM disc results in plenty of hiss, pops, and clicks which contribute to this frequency bump.

Remember—this acoustic recording was made by placing a horn near the orchestra and using a needle attached to the end of the cone to physically scrape soundwaves into the rotating wax or lacquer recording media. Brutal.

1920s

Though acoustic recording technology was in use from the late 1800s, the technological advances in electrical sound recording in the mid-1920s ushered in the beginning of the real commercial market for music. Western Electric pioneered the first electric transcription devices, featuring electrically amplified microphones driving a flywheel-propelled lacquer disc cutting lathe. Medieval in its simplicity, it allowed producers to go into the fields (literally) of the Deep South in search of new songs to capture.

I was listening to the soundtrack from the documentary series recently, and was marveling at how directly technology affects art, or in this case, music. If you listen to an early Jimmie Rodgers recording, such as “Waiting for A Train,” then compare it to one of the modern artists recorded for the American Epic soundtrack, like “Nobody’s Dirty Business” by Bettye LaVette, the sonic similarities are striking. Not only in terms of frequency response, but the performances share a similar balance between instruments.

Of course, much of that can be attributed to the modern use of a comparable electromechanical disc recorder and microphones available during the 1920s, but in each case the musical balance was achieved by physically moving musicians and instruments around the microphone to accommodate a harmonious balance, or “mix” of instruments.

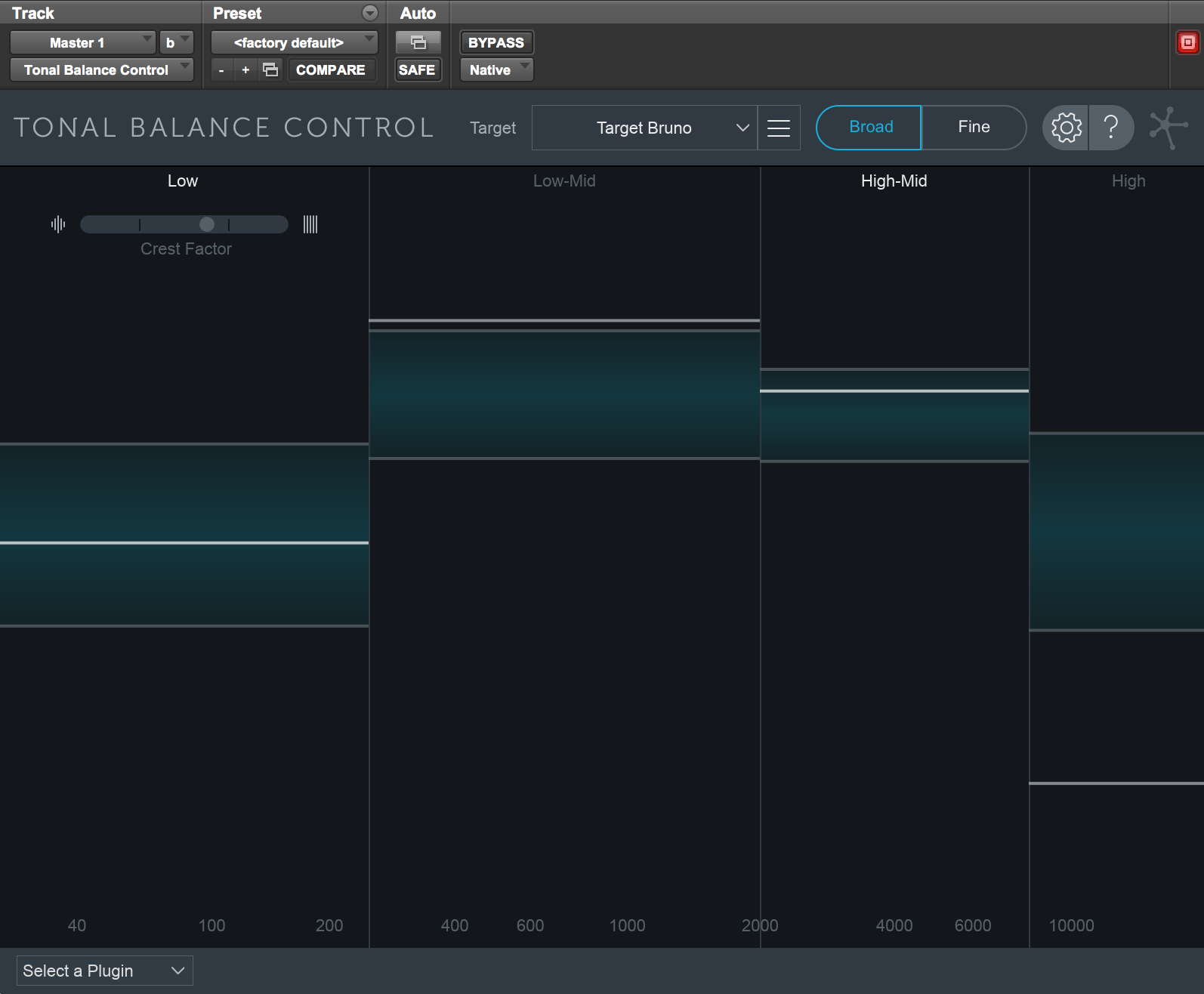

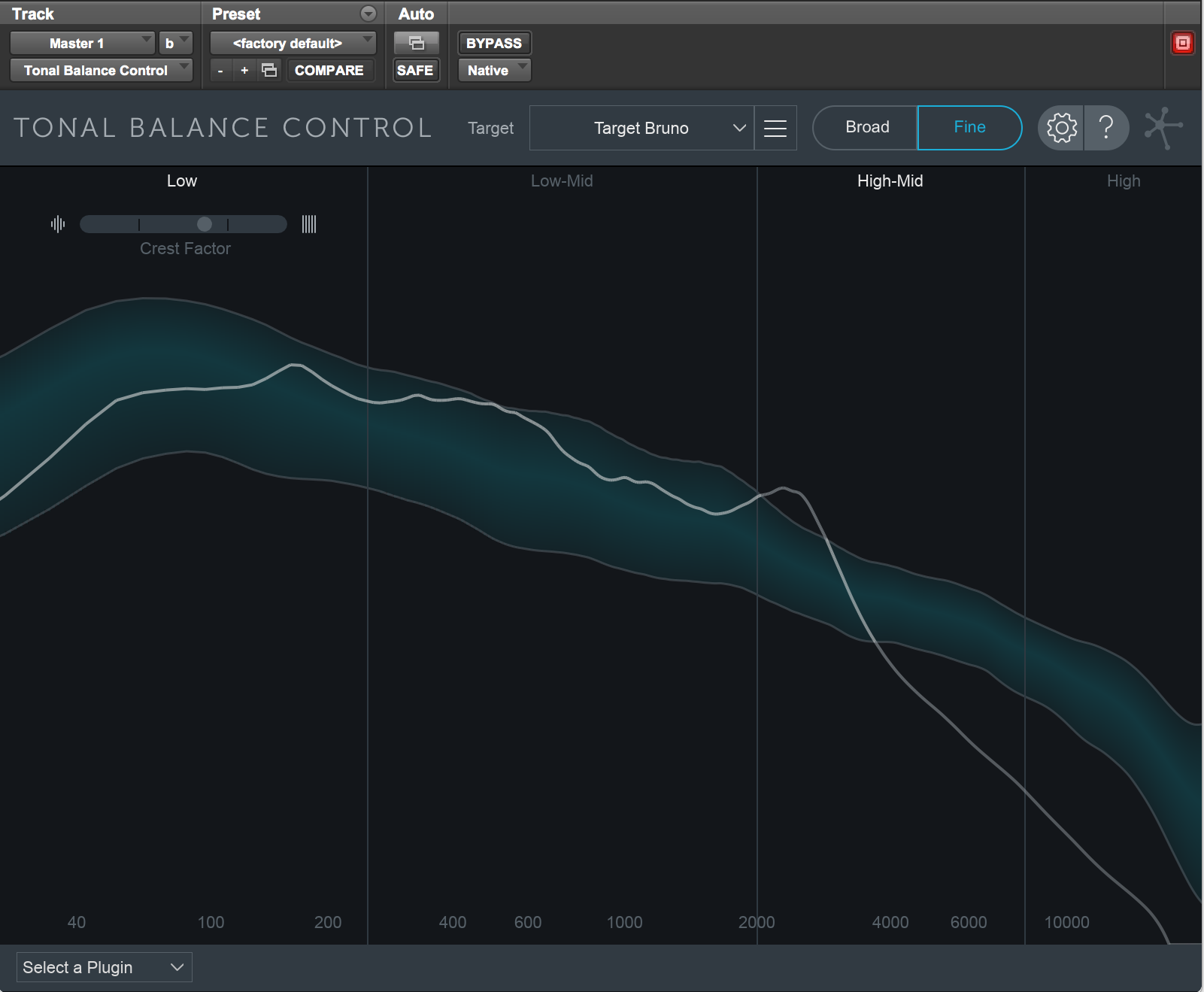

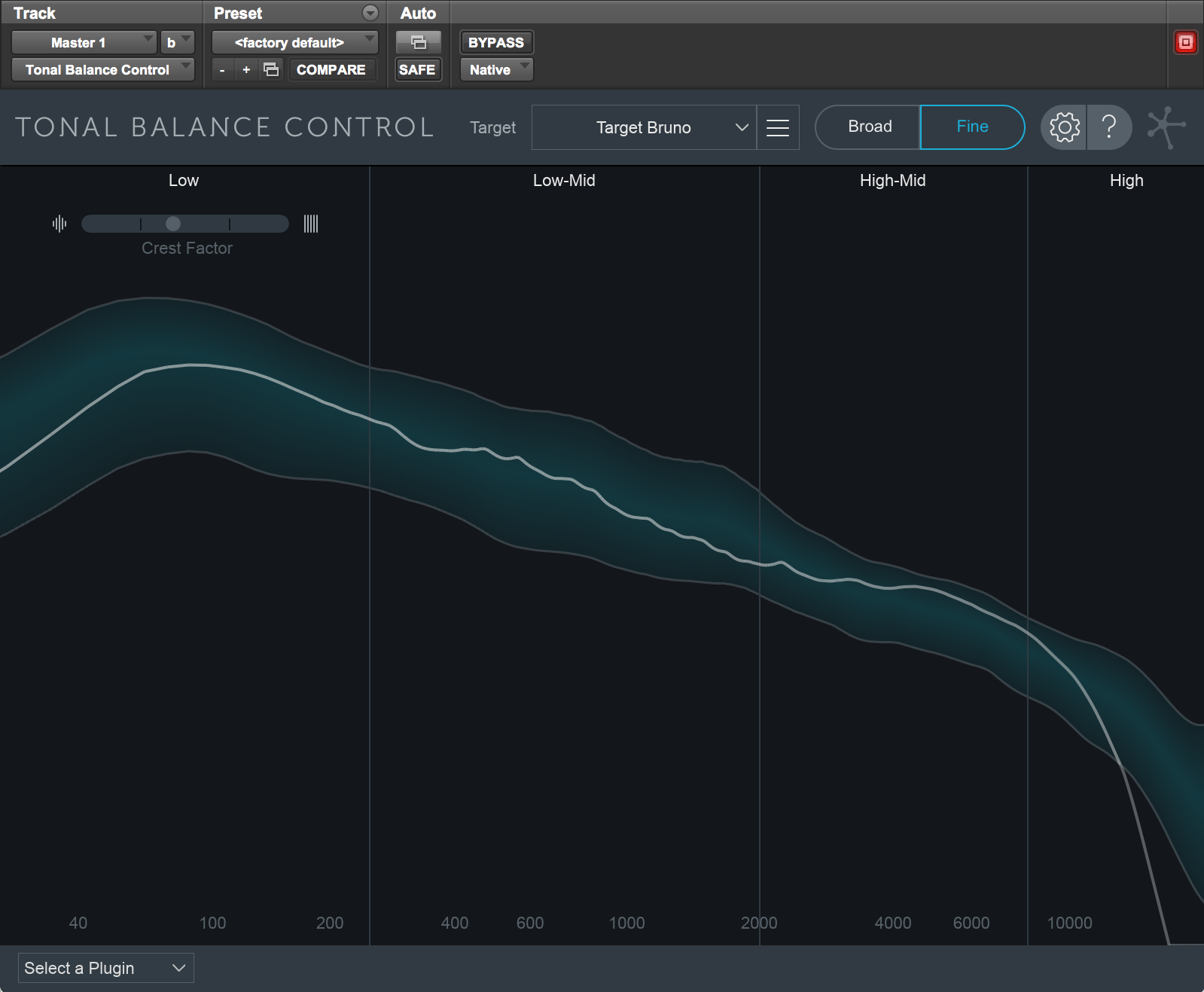

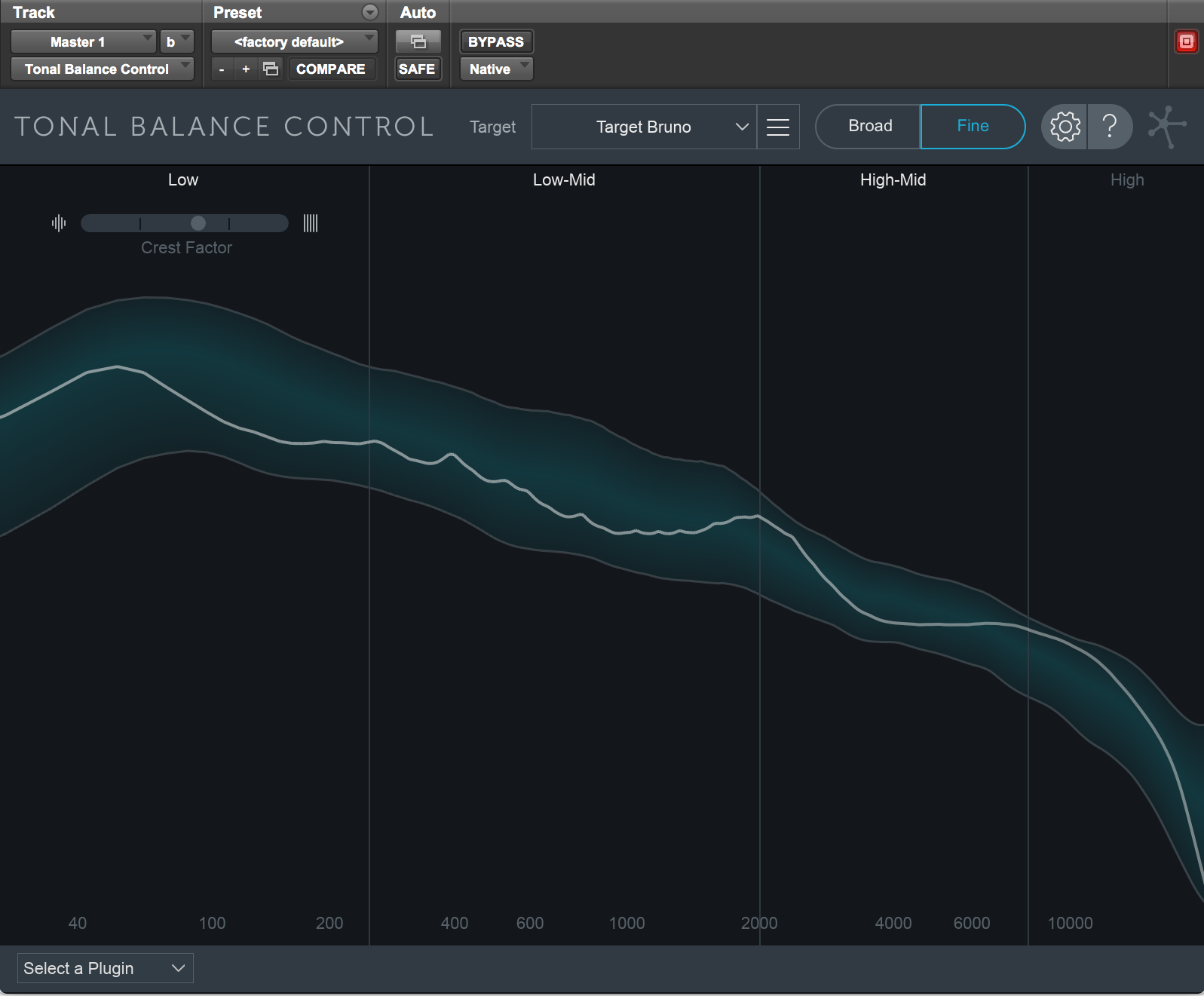

Using the Jimmie Rodgers piece from 1925, here are screenshots of the Broad and Fine views in Tonal Balance Control (viewing tonal balance at overall and granular levels).

Jimmie Rodgers, "Waiting for a Train" Broad View

Jimmie Rodgers, "Waiting for a Train" Fine View

It’s interesting to note that most of the energy in this recording is in the midrange, with a heavy roll-off above 3 kHz. Some of the bass frequencies are curtailed on commercial releases from this period, as acoustic record players did not have the ability to reproduce low frequencies reliably without distortion. I suspect that this reissue has had some noise reduction work done, since there is little discernible high frequency surface noise visible on the graph.

Recording technology was fairly consistent through the 1930s and 1940s, with artists cutting songs or “sides” directly onto lacquer-coated aluminum discs. Which meant that any mistakes trashed the lacquer master and subsequent takes had to be recut onto a new disc. Barbaric.

While the medium remained consistent, microphone technology improved, and miking techniques became more sophisticated as engineers began using more than one microphone to make up for gaps when placing musicians around a single mic.

It should be noted that all recordings up to this point have been mono.

1940s

Samples of popular 1940s recordings include The Mills Brothers “Paper Doll,” Artie Shaw’s “Frenesi,” Xavier Cugat’s “Brazil,” Glenn Miller’s “Chattanooga Choo Choo,” Bing Crosby’s “You Are My Sunshine,” and Duke Ellington’s “Take The A Train.” The sonic signature from these songs is remarkably similar, again due to the common recording equipment and techniques.

Duke Ellington, "Take The A Train"

All the songs from 1940s recordings mentioned above exhibit marked roll off of frequencies above 4 kHz… except for Bing Crosby's hit “You Are My Sunshine” from 1941, which has a tiny bit of extended high end >10 kHz as compared with the others. More on Bing in a minute.

The above pic is from Ellington’s “Take The A Train,” which has a huge bump in the low end. This 1941 recording featured the bass player prominently, and became a dance hall hit. Makes me wonder about rattling license plates… but I digress.

1950s

In 1947 Bing Crosby learned of a company called Ampex, which had just started to make magnetic tape recorders. When they showed him he could edit tape (unlike discs), he went nuts, to the point of investing $50,000 in Ampex to help them develop the technology.

Why? So he could pre-record his radio show (live at the time), edit the program, insert ads, create new versions for east and west coast broadcast—and listen to himself on the radio while he was on tour or at the beach. Possibly the very first instance of time-shifting!

Another benefit of recording on tape was the durability and wide frequency response of the medium. You didn’t need to worry about the needle jumping out of a groove, so low-end became less of a liability. This, combined with the introduction of mono LP records (12”, 33-⅓ RPM) by Columbia Records in 1948, changed the industry. 7” 45 RPM singles were not far behind.

While the first recorders were mono, Ampex soon made two, three, and four track machines, allowing producers and artists to experiment with overdubs and layering, previously unthinkable due to technical limitations. This was truly revolutionary. Especially in the hands of Les Paul, the genius guitarist. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Here is a snapshot of a quintessential 1950s recording—Elvis Presley’s “Don’t Be Cruel” from 1956. This is taken from a 45 RPM single.

Elvis Presley, "Don't Be Cruel" Fine View

You can see a good amount of bass, more than enough low-mids, and not much information above 4 kHz. Little improvement from the earliest recordings. Creatively amazing, sonically unimpressive.

But hold on a second. Look what Miles Davis was doing over at Columbia in 1959 with producer Teo Macero…in stereo, no less.

Here’s “So What,” from the iconic album Kind of Blue.

Miles Davis, "So What" Broad View

Well balanced low end, smooth low-mids, scooped upper-mids and extended high frequency response. This record is recognized by the US Library of Congress and the National Recording Registry, is in the GRAMMY® Hall of Fame, and happens to be the best selling Jazz record of all time.

Ladies and gentlemen, I think we just entered the "Hi-Fi" era.

1960s

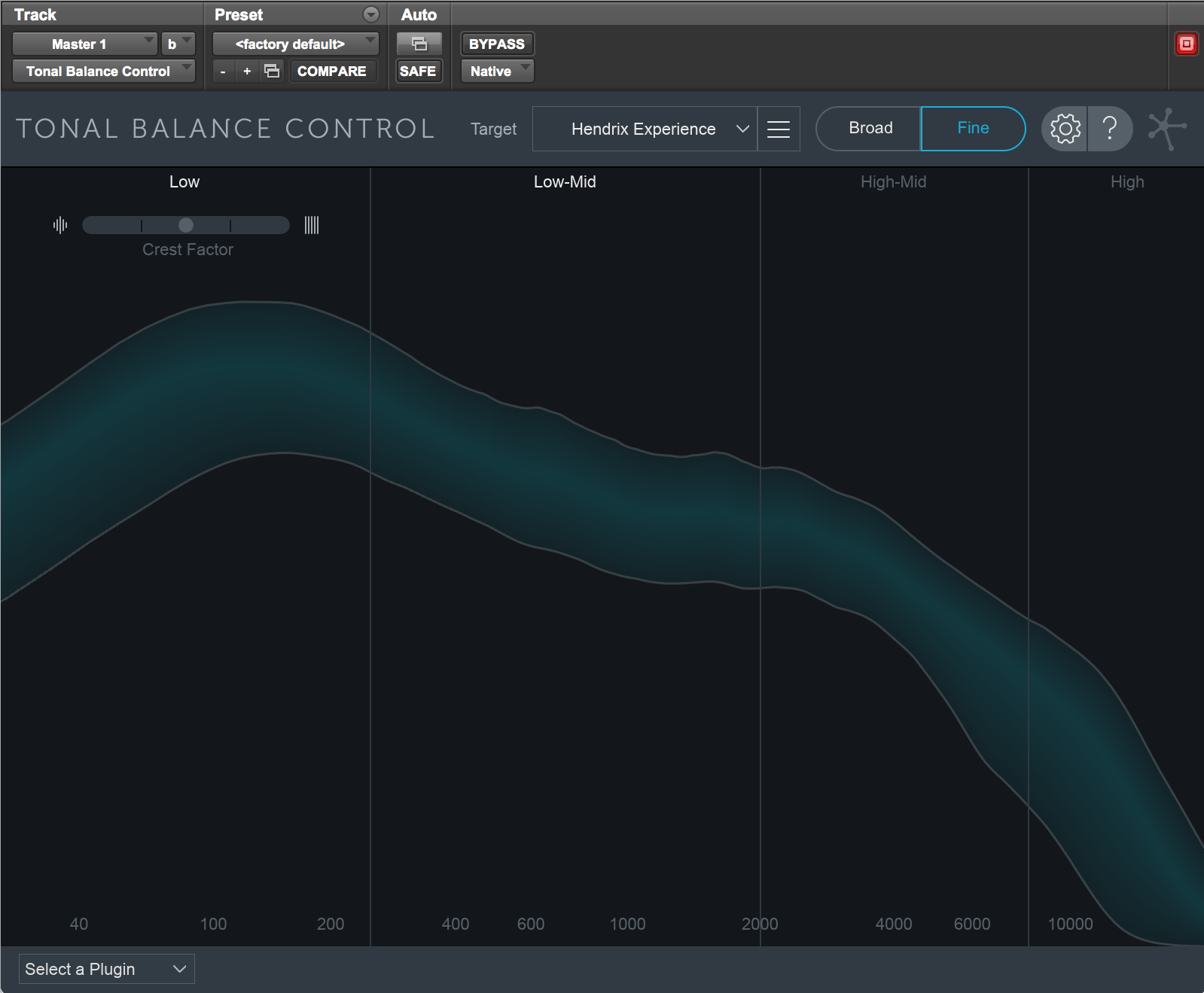

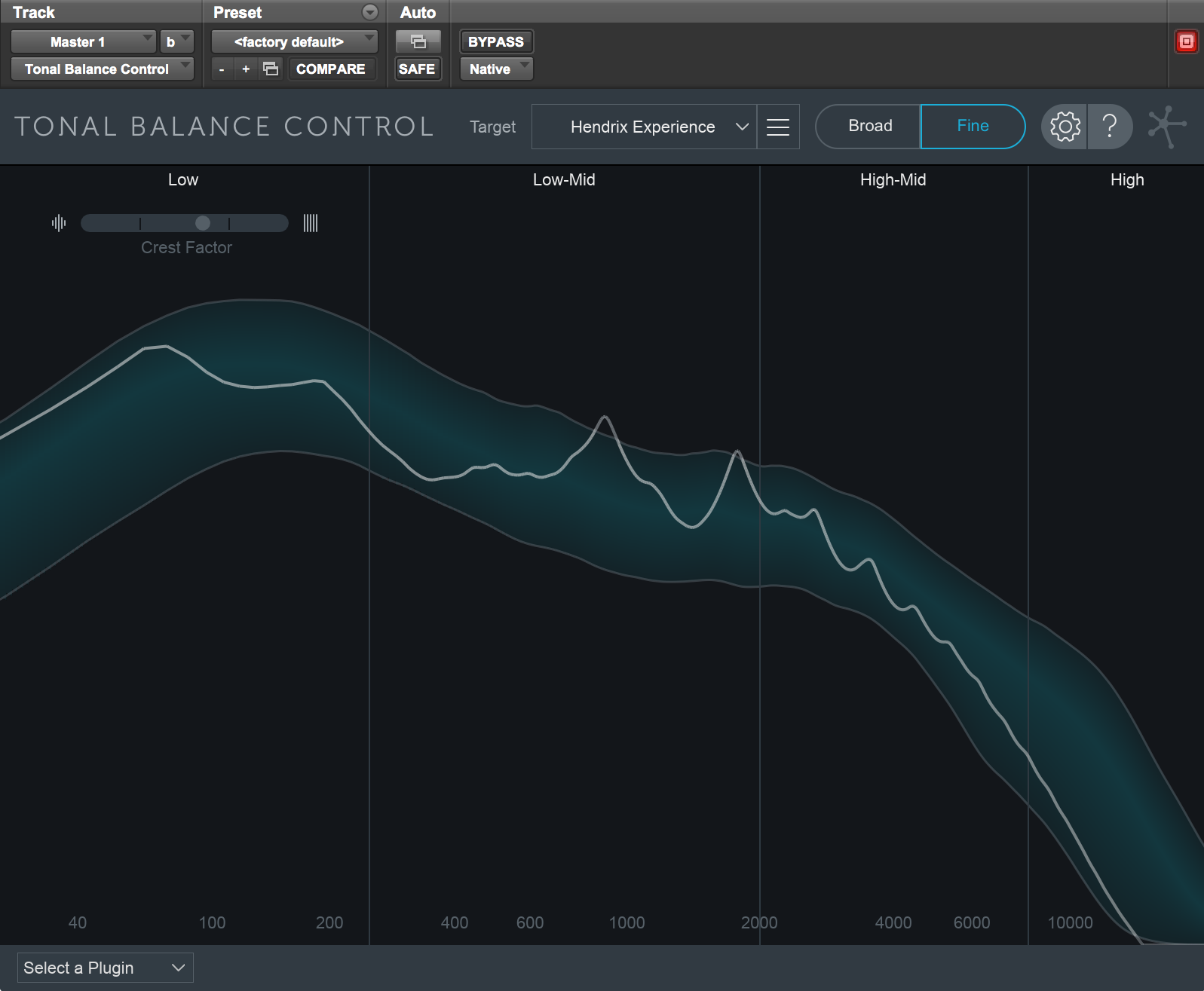

Why not two categories for the 1960s? Because you can’t really compare Percy Faith to Hendrix and Bruno Mars? Watch this. I made Hendrix his own reference curve from the Are You Experienced album.

Jimi Hendrix, Are You Experienced Reference Curve

Again, here is Bruno’s curve below...

Bruno Mars "24 Karat Magic" Reference

Jimi’s low-end peak is centered around 100 Hz, whereas Bruno is centered around 60 Hz. Jimi’s mids are peaked at 2 kHz (guitar, duh.), and his high-end starts to roll off around 10 kHz, while Bruno extends all the way out to 20 kHz.

Les Paul may have invented multitrack recording, but Hendrix (and the Beatles and the Beach Boys) took it to a whole new place. Sixteen-track recorders, condenser mics, high gain amplifiers, and high fidelity/low noise electronic components all contributed to what would become the modern standard for recording music.

Oh yes, Percy Faith. “Theme From A Summer Place” vs. Jimi Hendrix...

Percy Faith, “Theme From A Summer Place”

And vs. Bruno Mars...

Percy Faith, “Theme From A Summer Place” vs. Bruno Mars "24K Magic"

Percy can hang with Bruno in the low-end, but what the heck is going on in the upper mids here? I’ll tell you: screaming violins. Wretched, banshee hellhound violins like nothing you’ve ever heard before. You need to check this stuff out. The high end on Percy is somewhat lacking, though somewhat a relief, considering the unholy “Psycho”-style racket going on in the upper mids. Truly frightening.

1970s

Enter analog 24-track tape with noise reduction, high-end mixing consoles, the pinnacle of post-war audio technology, according to many.

Steely Dan challenged all the standards. If the technology didn’t exist to get the sounds they heard in their heads, they would invent it. (Actually, Roger Nichols would invent it.)

“Aja” has to be one of the Dan’s finest recorded moments. Here we compare it to Bruno:

Steely Dan, "Aja"

This follows the Bruno formula pretty closely (or vice versa), and has a balanced frequency response all the way up to probably 16 kHz.

Compare this to the #1 song from 1976, Rod Stewart’s “Tonight’s The Night.”

That’s Rod’s voice there, at 650 Hz. Just saying. You can judge the rest.

1980s

Digital recording is introduced, and all but takes over from analog tape on the pop music scene. Billy Joel has the first major all-digital release via commercial compact disc with his album 52nd Street, but Peter Gabriel learned to use the expanded dynamic range to maximum advantage. Digital recording through a state-of-the-art SSL consoles made possible lots of sonic experimentation and led to a new vocabulary of sounds, including the once-cool, then-dreaded, now hipster-refreshed gated reverb.

While the introduction and subsequent popularity of the CD led to the temporary demise of vinyl, there were accusations of “cold,” “brittle,” and “harsh” sound quality when discussing the characteristics of early digital recordings. Frankly, I loved CDs (and still do). Those of us who grew up with super-noisy vinyl quickly learned to appreciate the master-quality sound of CDs. It was the mastering and encoding process that lent the harsh artifacts, but it didn’t take long to tame the beast.

Here is Peter Gabriel’s “In Your Eyes,” one of my desert island recordings.

Peter Gabriel, "In Your Eyes"

There’s that smiley-face EQ curve we all strove to achieve in the 1980s. Notice the cessation of all high-end activity above 16 kHz? Thank you, early digital recorders. The Nyquist theorem states that you must brick-wall filter frequencies at ½ the sample rate in order to avoid aliasing noise. If this was recorded at 44.1 kHz sample rate, you would need to kill off everything above 22.05 kHz. Looks like the mastering engineer played it safe. Still, an amazing recording.

One of the truly awful things about early digital is that we invested an entire generation of music in the limited frequency bandwidth formats available at the time. Now we can sample up to 192 kHz, leaving us an effective bandwidth of 96 kHz of usable frequency response. (Not that I can hear anywhere near that high, but the local dogs find it entertaining.) You won’t hear any of that on 1980s and 1990s digital recordings.

1990s

While the hip hop movement grew in the 1980s, artists really found their creative niche in the 1990s. As technology improved, Pro Tools became an affordable and highly experimental platform for the creation of music without the need for a huge recording studio and all of the related gear.

At the opposite end of the musical spectrum, the Grunge movement embraced 1970s recording equipment and techniques, and used the dark sound of 15 IPS 24-track tape as a part of the musical idiom.

Let’s compare one of each. First up: Coolio, “Gangsta’s Paradise.”

Looking good, Coolio. A little truncated at the top, but better than the 1980s.

Here are our hometown heroes, Soundgarden, with “Black Hole Sun.”

Interesting, almost a smiley-face EQ. Lots of high-end, but a roll-off around 16 kHz. This was an analog recording, mastered for CD release.

2000s

With the popularity of home recording, the consistency of production quality has become more random. While on the highest levels of pop you have Max Martin and his cadré of hitmakers using the best studios and most exotic boutique mics and kit, you also have folks making huge hit records in their homes.

From Bon Iver’s “Blood Bank.”

To be fair, Adam recorded this in his parents’ basement, then mixed this in a pro studio. Pretty good capture though, I would say. Look at all that 20 kHz.

2010s

Interestingly, I now have more processing power and recording resources on my phone than my million-dollar digital studio built in the mid-1990s. Not to mention that the IOS app GarageBand boasts higher bit/sample rates and greater track counts than my stacks of DA88s. Not that I’m bitter or anything.

People are actually producing complete tracks on their phones. Steve Lacy produced beats for Kendrick Lamar’s latest album…on his iPhone. Check out “Ryd.”

Steve Lacy, "Ryd"

Except for a little drop in the high-end, this looks pretty good. For an iPhone-only production, this looks fantastic. Also consider that Steve played all of the instruments himself using only the iPhone and an inexpensive guitar/bass interface.

So there you have it—an abbreviated version of music through the ages.

Time permitting, it would be heaven to go through my music collection to analyze all of the different eras and styles of music, from Classical to Klezmer, and everything in between. Today’s blog is just the tip of the iceberg. I hope you discovered something new about the way your ears hear things, and how to visually recognize “that sound.” Play around with your favorite music, and while you’re at it, check out some of the artists and their music as featured in this article. It was a joy to discover—or rediscover—some of these gems. Maybe they will become reference material for your future work as well.

Until next time, ave atque vale!

Additional Resources

Library of Congress National Jukebox, 19th and 20th Century sound recordings

Documenting the first electric recording systems of the 1920s

The Nyquist Theorem http://microscopy.berkeley.edu/courses/dib/sections/02Images/sampling.html