Stems and multitracks: What’s the difference?

Learn all about the difference between stems and multitracks and how to use stems in music.

I can’t tell you how many clients confuse the terms “multitracks” and “stems,” often to their own financial distress. It goes like this: a client will say “I want a stem master” and then proceed to send me the multitracks for a mix, leading to an uncomfortable conversation in which I have to explain that what they’re asking for is something both different and more costly.

In this article, we will define the two terms once and for all. Then we will get into the many reasons to utilize stems in your workflow.

What are stems in music?

TLDR: Stems are a mixed group of related tracks

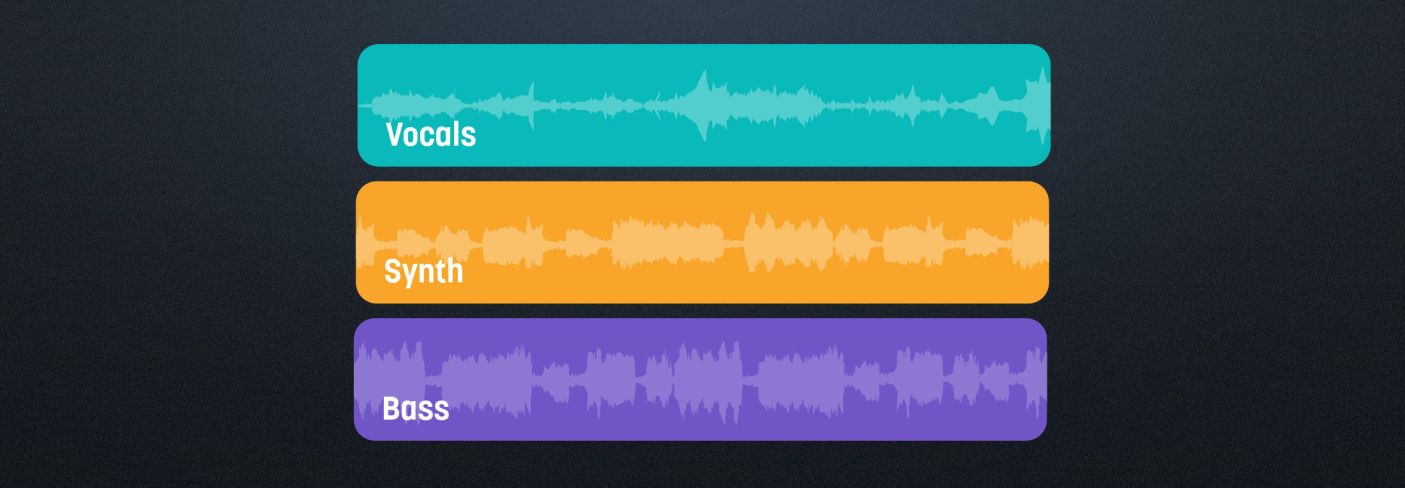

A stem is a group of related—and most importantly—mixed tracks printed together as a single file. A drum stem is all of the drums. A bass stem is every bass part in one stereo track. And so on.

Here's an example to make it clearer:

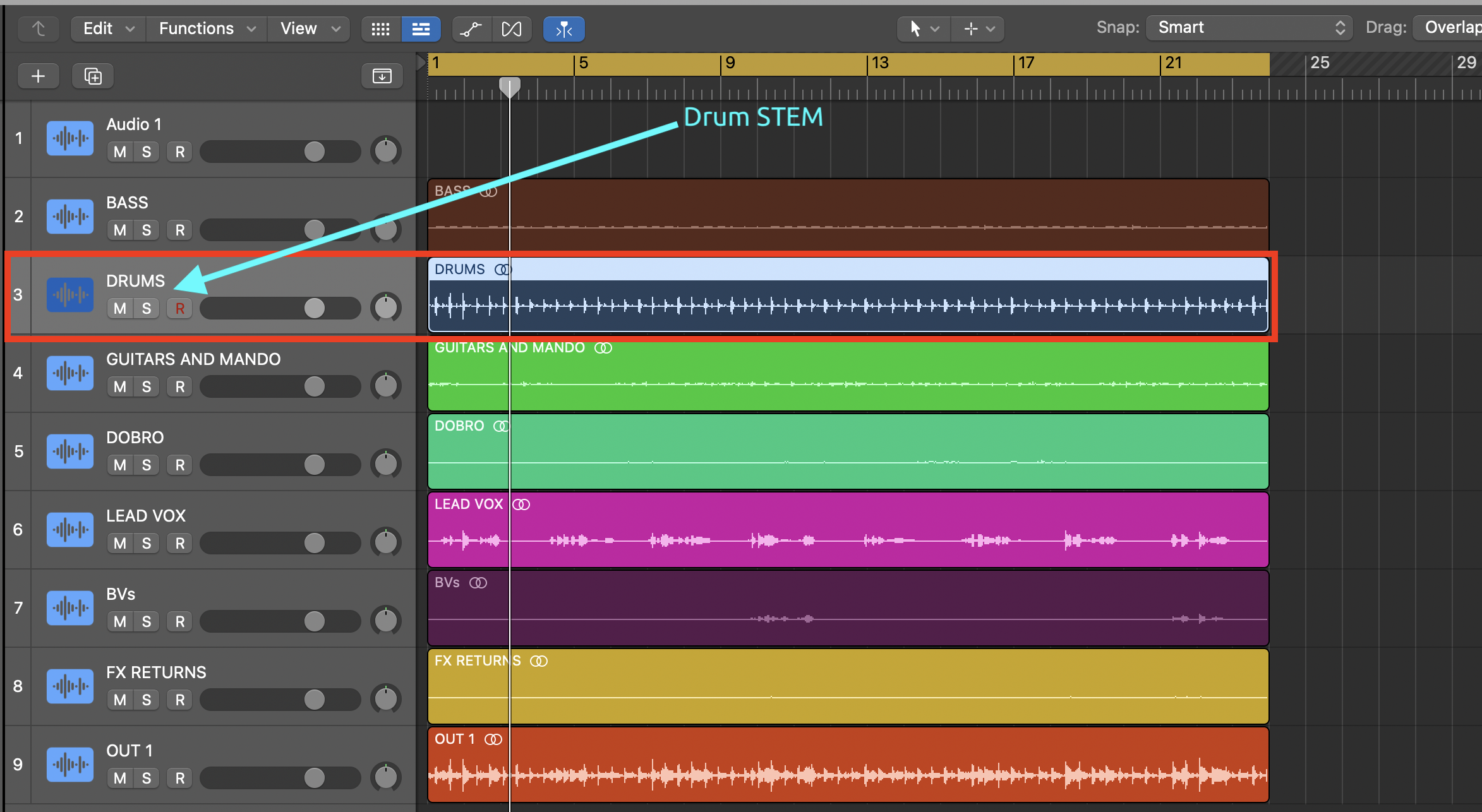

A kick drum mic, a snare mic, and two overhead mics: we record each of those to its own individual audio track.

Highlighted drum tracks

Take the submix of the entire drum kit and render it into a single stereo file? That’s a stem.

Highlighted drum stem

A stem can be a mono, stereo, or multichannel file, depending on the format you’re working in. But it’s always a mini-mixdown, a microcosm of the mix in total.

Ideally, if we were to have a drum stem, vocal stem, instrument stem, and bass stem, it should add up to—and sound exactly like—the mix as a whole. It would even be perfect if they nulled, as shown here:

If a producer calls me and says “I have the stems for a master,” I will expect four or more already-processed stereo tracks that, taken together, will comprise a mix ready for mastering.

So what do we mean when we say “multitracks?”

TLDR: Multitracks are the raw, unprocessed individual tracks that you use to mix

The term “multitracks” comes from the term “multitrack recording,” in which a band of musicians records to multiple tracks at the same time.

From what I can tell, “multitrack” and “multitracks” are interchangeable, and they refer to the same thing: the raw tracks you’ll use for mixing.

A mix consists of all the individual elements of a song. Usually each element has its own dedicated track—kick in, kick out, snare top, snare bottom, and so on.

Some tracks in the mix may be mono, while others are stereo. Some might have been recorded from microphones or direct inputs, whereas others might be arranged in a sampler, programmed in a sequencer, or played in MIDI.

If a producer calls me and says, “I have the multitrack for you,” I’m expecting individual tracks for each discrete element. That, or a DAW session with all those elements laid out.

What do we use multitracks for?

Multitracks are meant for the mix engineer. The band, artist, label, or producer sends a multitrack session (the “multitrack”) to the mixing engineer, who delivers a stereo or immersive mix-down of the project for the client to hear.

The mixing engineer might also be asked to deliver stems.

How to create stems

Different DAWs, different methods

Every DAW is a bit different when it comes to stem creation, but regardless of the software, it’s easier to create stems if you route all the associated tracks to the same bus/auxiliary return, hereafter referred to as a “submix.”

If the drum tracks (kick, snare, etc) are all outputting to their own submix, it’s much easier to generate stem using that aux.

How to create stems in Logic:

Step 1: Click the submixes you want to export in the Arrange window.

Step 2: Highlight the time selection you’d like to bounce

Step 3: In the app menu, click “File -> Export -> Tracks as Audio Files”

Step 4: Choose your options (I like 32-bit, record only the highlighted cycle)

Step 5: Hit Enter and make your stems.

How to create stems in Pro Tools:

Step 1: Click the submixes you want to export in the Edit window.

Step 2: Highlight the time selection you’d like to bounce

Step 3: In the app menu, click “Track -> Bounce” (or use the key command “shift+option/alt+command B”)

Step 4: Choose your options (I choose 32-bit interleaved, and I keep the automation on).

Step 5: Hit bounce and make your stems.

How to create stems in Reaper

Step 1: Click the submixes you want to export in the Arrange window.

Step 2: Highlight the time selection you’d like to bounce

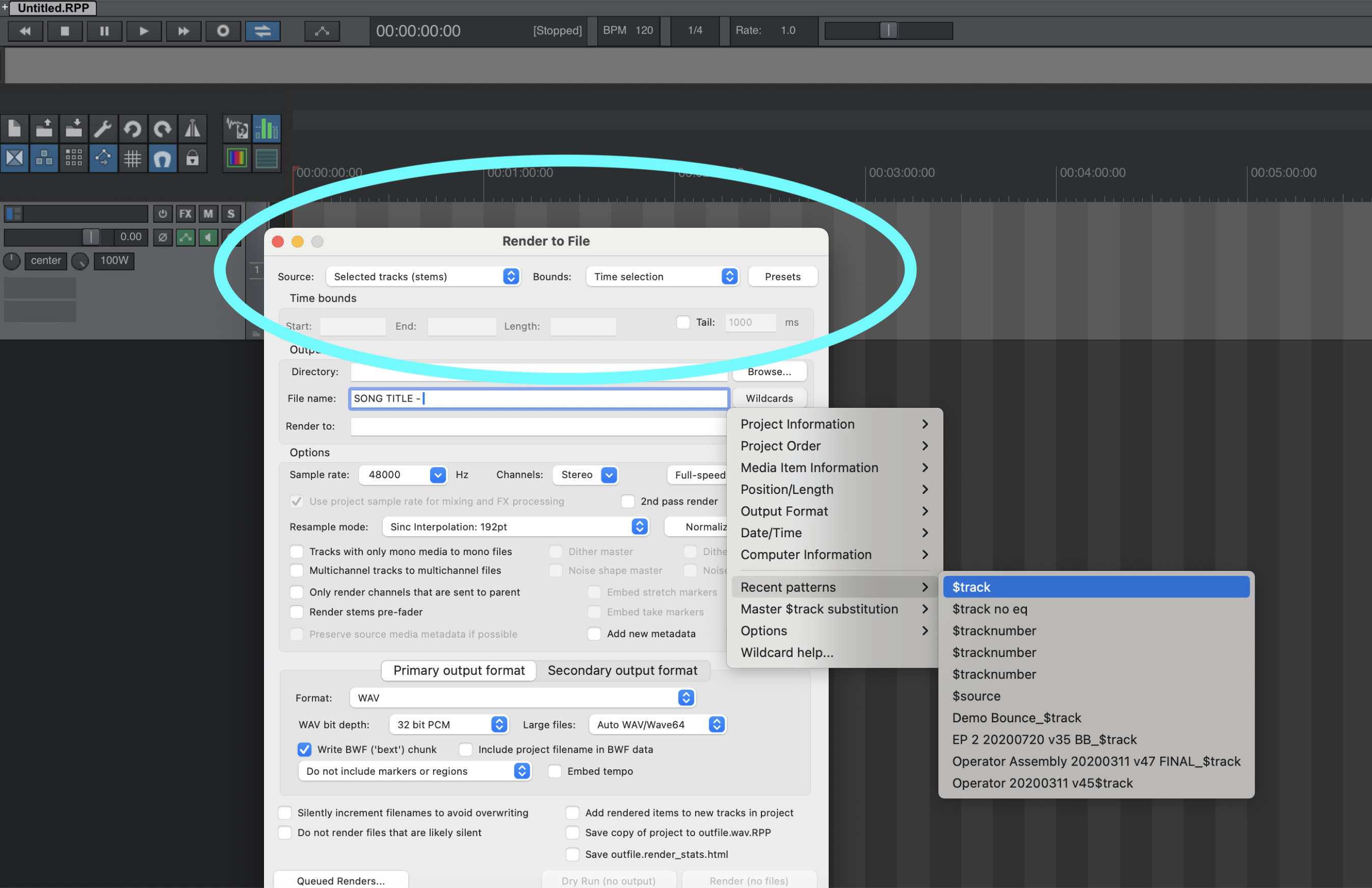

Step 3: Choose the following options from this screenshot (I’ve circled the most important things to consider):

Reaper export

Step 4: Choose the file options you want from this window (again, 32-bit wav is great)

Step 5: Hit Render

Different ways to group tracks

It’s common to see a drum stem, a bass stem, a vocal stem, and an “everything else” stem; that’s why RX 11 Music Rebalance has those categories for its automatic stem separation.

But it’s okay if you’d like to get more specific than that. Some engineers stem the instruments out by type (drums, bass, synth bass, acoustic guitar, electric guitar, etc). Some print their stems wet (with the associated effects) and some print them dry (no effects), offering with the reverbs and delays on their own stems.

Personally, I like to have various options at my disposal for rendering stems. I think it should be up to the artist if they want the vocal reverb with the vocals on the same stem.

To make this work, I’ve generated a rather complicated template, and I’m happy to show you it in the following video. Please note, it’s not an entirely original creation. Some of it is my own doing, and some of it is influenced by a variety of different engineers I know and love.

Different processing factors to consider

You have to keep in mind that if you’re using nonlinear stereo processing on the mix as a whole, the stems are not necessarily going to add up to/null with the original mix (nonlinear here meaning compression, saturation, and limiting).

Think about it: nonlinear stereo mix bus processing is reacting to everything: the kick is affecting compression across the whole track, for example.

Here’s the thing though: It’s rare that someone is going to want the stems to equal a stereo-bus that has been heavily compressed or limited (We’ll get into why this is in the next section).

If they do want stems that equal the original stereo-mix, complete with nonlinear processing, you can make that work, provided the processors you use have a sidechain input. Simply print the entire mix without stereo processing, and use the result as the sidechain input for all of your stereo bus processors.

What do we use stems for?

There are multiple use-cases for stems in modern production. Let’s cover them now

Creating radio edits and alternate versions

It’s not uncommon for songs to have radio edits, either for duration or explicit language. It’s also common for artists not realize they need to make these versions in the mastering process, rather than the mixing process.

Alternate versions can be handled rather quickly at the stem level: it takes no time to cut out or bleep and expletive at the stem stage. If you don’t plan on having stems, you’ll either have to mix several versions of the song at the outset, or dig back into your mix session at a later date.

Both of these things cost time, and therefore, money. Printing stems is the organized way of handling this issue, taking less time for you and costing less money for your client.

Creating remixes

Say someone wants to do an EDM remix of a song you mixed. It’ll be much easier for them to do this if they’re working off stems, rather than your multitrack. That way they’ll have perfect access to sounds they like in your mix, and they won’t have to reverse engineer them, which can be quite tedious.

Creating performance tracks for the artist/band

Many artists play tracks, and it’s nice for them to have high quality versions of these tracks, rather than the raw elements they supplied for mixing. If you send them stems, you’re ensuring their public performances will sound much better.

Creating versions for derivative media

As artists and labels sometimes ask for clean/radio edits, they might also seek a sync deal in television or film.

The deliverables for these sync deals often require stems, and that makes total sense: the song is going to need to fit the edit of the scene. Making the song conform to the scene falls squarely on whoever’s editing the derivative media. If that person has stems, they can mute the vocals when they conflict with dialogue, and leave in the big rousing chorus during a cinematic montage or something like that.

Giving the mastering engineer more to work with—should they ask for it

Yes, your mastering engineer should be able to work with a stereo file, but I’ve been in both chairs, and I can tell you, sometimes it’s so much easier for them to have the stems.

An example: sometimes the bass is just so loud that you will not get a competitive level out of the track no matter what you do. EQing the whole mix will destroy the energy, compression will incur distortion, multiband compression will kill the groove, and limiting will make the whole mix fold. If you could just have the bass stem, you could turn down that bass instrument two or so dB and everything else will work fine.

In this case, the mastering engineer might ask for stems, and use them in a variety of ways. Here’s my go to move upon receiving stems: I import the offending bass stem, flip the polarity on it, and see if it cancels the instrument out from the mix completely. If it does, I don’t need the rest of the stems: I can use the polarity-flipped offender as a fader to control the level of bass in a rather transparent manner.

Also keep in mind that some world-class mastering engineers openly extol stem-mastering, citing its abilities to achieve a less destructive master at commercial loudness targets.

Here’s why: if loudness in mastering is your goal, it can be easier to minimize distortion across the stem level while staying true to the character and intention of the mix. Otherwise, the ME might have to do something drastic to get to that mandated target—like chopping out a lot of bass to keep the limiter from farting out. No one wants that.

It doesn’t mean your mix is bad if a mastering engineer asks for the stems, by the way. It usually means some element of the mix doesn’t work with the annoying amount of dynamics-taming commercial music can demand. Under the constraints of commercial clipping and limiting, a different balance of the stems can actually sound more like the original mix than the original mix!

Overdubbing easily in collaborative settings

Sometimes musicians work in different studios, and it can be a giant pain to send multitracks back and forth. Think of the band Tool, who record all their instrumental parts over the course of years before the singer ever touches the songs. Do you think MJK opened up a full pro tools multitrack when recording the vocals for Fear Inoculum in his home studio? Only Joe Berrisi knows for sure, but I’m willing to bet they worked off stems.

Streamlining collaborations

The same methodology goes for collaborative projects in general. Trading compositional ideas back and forth with a bandmate? Stems might be easier to work with than oodles and oodles of multitracks.

Creating immersive versions

They tell me atmos is here to stay in the music business (though I have personally never heard anyone clamor for the atmos mix of anything in my professional or personal life). Even so, an artist might want to release their work in Atmos, and atmos mixes are usually created from—you guessed it—stems.

Archiving the project

One likes to think the work they do matters, and that it might want to be revisited in future times, long after one is gone. Still, one has an ego and would like to have some say in derivative projects. For this reason, archiving the project as stems is a great option.

Creating revenue opportunities

You can and absolutely should charge for the creation of stems. It’s a value-add to your deliveries, and if an artist is serious about their craft, they will understand that more services cost more money.

What about stem separation technology?

If you’ve come to this article after googling “how do I find the stems of a song,” then this section is for you. You’ve got two choices when it comes to “finding” the stems of a song that are not fully in your possession.

The first choice is to search the Internet to see if the stems exist in any legal form online. If they do, download them (and hopefully pay the artist for the privilege of doing so).

Another option is to use RX's Music Rebalance stem separation technology to automatically split the track into stems (vocals, bass, drums, and other).

When in doubt, just ask!

If you aren’t sure what your client or collaborator wants, the best thing to do is simply ask.Where the terms have become so interchangeable, it’s best to clarify before hitting the export button.

If they’re only needing stems, you can save yourself precious time and energy not exporting, labeling, and organizing every individual instrument for a multitrack. But, if they do want the multitrack, it’s going to save some back-and-forth if you accidentally send them stems instead. The bottom line: when in doubt, ask!

Now that you know the difference between music stems and multitracks, you’re ready to get into deeper topics—so definitely peruse the following articles linked below.