How to Choose Chords for Your Melody

If you understand the relationship between melodic notes and two core theoretical concepts, any melody you write can have a happy home. To choose the right chords for your melody, you will need to transcribe, analyze, and experiment.

An often complicated aspect of writing music is unpredictable inspiration. It can strike anywhere and any time, and what your inspiration yields will always be different.

Where each musician begins their songwriting process also varies. Some prefer to write a chord progression or a rhythm first, while some pen lyrics before any music comes to mind. So what do you do when inspiration strikes in the form of a melody? To move forward with an isolated melodic idea, we should understand two vital concepts that will prove essential in choosing the right chords for your melody.

Diatonic chords

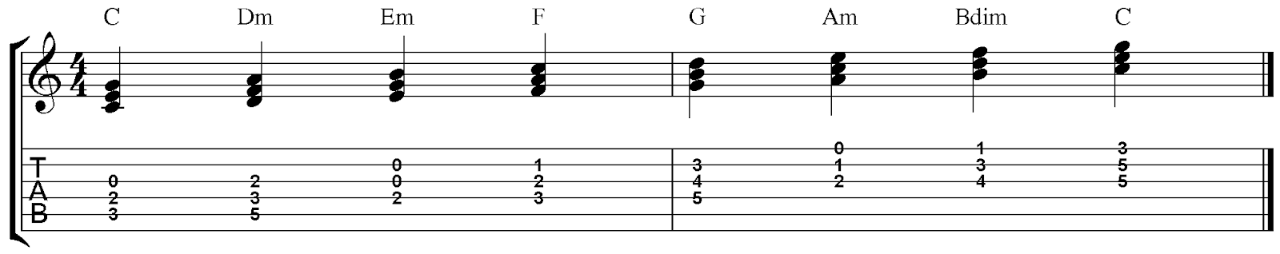

Most melodies are based on a major or minor scale that correlates with the key of the song. Say your melody comprises the notes in a C major scale (C—D—E—F—G—A—B); each one of those notes is the tonic, or root note, of its own chord. These chords are called diatonic chords, and they play an integral part in assigning chords to a melodic note. This may seem a bit confusing, but the diagram below can shed a little light on this concept.

C major scale

Each diatonic chord is made up of three notes within its scale: a tonic, a third, and a fifth. For those of you who don’t read music, the notes in the C triad above are C (tonic), E (third), and G (fifth). The second note in the C major scale is D, which is assigned to D minor (D as tonic, F as third, and A as fifth). The third note is E and is assigned to E minor (notes are E, G, and B).

In short, the second, third, and sixth notes in the C major scale (D, E, and A) are minor chords, while the tonic, fourth, and fifth notes (C, F, and G) are major chords. The seventh note (B) is a diminished chord, which means it is comprised of a tonic (B), a minor third (D), and a flat fifth (F).

Relative major/minor keys

For every scale there is a relative major or minor scale that shares the same notes. To find the relative minor scale to a major scale, start at the tonic and count a half step and a whole step down. In the case of C major, the relative minor key is A minor (C to B is a half step, B to A is a whole step). To find the relative major of a minor scale, start at the tonic and count a whole step and a half step up (A to B is a whole step. B to C is a half step). The diagram below shows the relationship between a C major scale on the top and an A minor scale on the bottom.

The first thing you’ll need to do with your melody is get it out of your head. If you’re close to an instrument, try transcribing it. By placing your melody to a visual aid, you can analyze the notes that you’ll be working with.T

Now that we’ve brushed upon the theory, let’s break down some examples and explore methods in choosing chords for a melody in C Major (all audio examples in this piece were recorded using Spire Studio).

Example A

Start by finding a tempo that matches your melody by using the Tap feature in Spire Studio’s metronome. Then record your melody. This melody is at 90 bpm.

In this 6 bar example, the melody is derived from the C major scale. Let’s break it down further to see what notes are in each measure.

Measure 1: E, D, C

Measure 2: G, A

Measure 3: F, A

Measure 4: A, G

Measure 5: C

Measure 6: C

The idea is to match the notes in each measure with a diatonic chord.

In measure one, we have E, D, and C. The chords that share these notes and best fit the melody are C Major and A Minor. Let’s pick C major for the first measure to establish the major key.

Measure 2 can use E minor, A minor, G major, and C Major. Let’s pick E minor.

Measure 3 can use F major and D minor. Let’s use F major.

Measure 4 can use A minor and G Major. To create a succinct ending, let’s use A minor on the A, and G major on the G.

Measures 5 & 6: use C major to signify the ending.

The chord progression: C Major / E minor / F Major / A minor - G Major / C major

The melody on top sounds like this:

Keep in mind that you have plenty of options. For this melody in a major key, these chord progressions also work and fit the melody:

C Major / E minor / D minor / F Major - G Major / C major

C Major / A Minor / F Major / C Major

C Major / A Minor / D Minor / F Major - E Minor / C Major

Example B

Using the same melody as Example A, we can use the relative minor key of C Major to create a completely different feel. Since we’ve established that A minor is the relative minor key of C Major, let’s make A minor the chord in the first measure.

Let’s reference back to the different chord options for each measure in Example A and choose a different set of chords:

Measure 1: A Minor

Measure 2: E Minor

Measure 3: D Minor

Measure 4: F Major - E Minor

Measure 5: A Minor

Measure 6: A Minor

A minor / G major / D minor / F major - G major / A minor

A minor / E minor / F major / D minor - E minor / A minor

A minor / G major / F major / F major - G major / A minor

Conclusion

By better understanding the relationship between melodic notes and diatonic chords, every melody that worms its way into your ear can find a comfortable habitat to call home. Next time inspiration decides to strike, just remember to transcribe, analyze, and test out your options. You can also demo all of your chord and melody options by recording them with the free Spire app for iOS. Happy writing.