8 Killer Reference Mixes for Hip-Hop

Don’t know what to reference while mixing hip-hop? Here are eight great tracks to reference, plus their free Tonal Balance Control curves.

Download Hip-Hop Curves Demo Tonal Balance Control in Ozone 9

Download the Tonal Balance Control curves of the songs mentioned here to reference for your next project.

To load the curves, download them and move them to the Target Curve folder, which you can locate in the following path on both Mac and PC /documents/izotope/tonal balance control 2/target curves. You will then be able to access the curves directly in Tonal Balance Control.

Well, well, well, what do we have here? Another article to supply you with references. This time we’re diving into hip-hop—and what a wide array of material do we present to you today! Without further ado, let’s get into it: here are eight great references to check out when mixing, producing, or mastering hip-hop. Don’t forget to download the Tonal Balance Control curves here.

1. Do It Now

Artist: Mos Def Feat. Busta Rhymes

Mixing: David Kennedy

Mastering: N/A

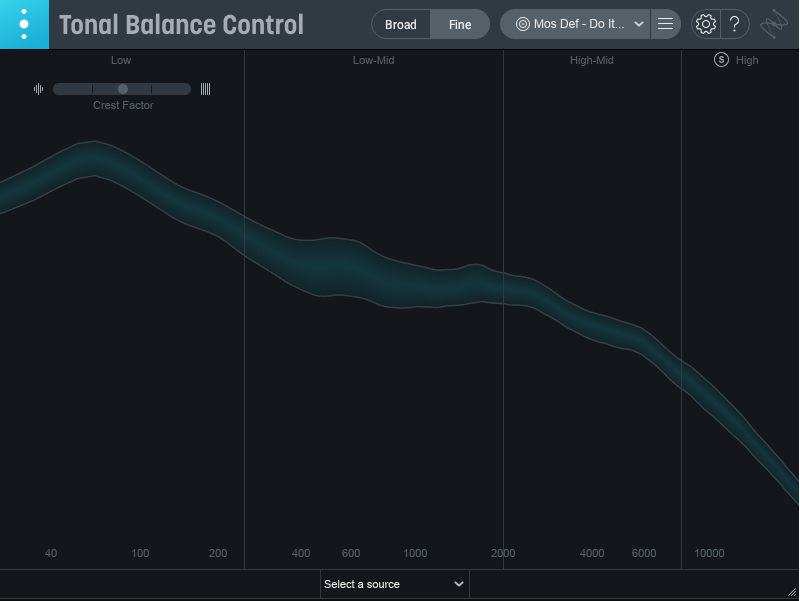

Tonal Balance Control curve for "Do It Now"

Yes, this tune is an old one, but it’s still a good lesson in how to handle content in a mostly monaural fashion. This is still a worthwhile endeavor: a hip-hop track ought to retain mono compatibility to compete in various locations—anywhere from the car to the club.

This track does feels mono, and looks especially mono when you view it in a meter:

Stereo field of “Do It Now”

However, if you listen to the tune and then reflect upon it within the playback of your memory, its monaural aspect doesn’t tend to stick with you—it doesn’t feel small, closed in, or pinned down.

This is because of the track’s frequency balance. All of the elements have their own place, and while the bass doesn’t sport an overt high-mid definition, you can still hear it quite well. Any high-midrange is ceded, instead, to the crack of the snare, and the vocal (of course). Still, the notes of this undefined bass are intelligible and don’t conflict with the kick drum.

In the Tonal Balance Control curve above, you can see these elements clearly: the kick around 60 Hz, the snare’s meat around 200 Hz, vocal heft circling around 500 Hz, and vocal cut at 2 kHz.

That the grooving yet balanced stacking of kick, bass, drums, harmonic instruments, multiple vocals, and effects was accomplished largely in mono is a testament to how good the mix is. Still, sometimes an element does give us a more stereo feel, and this helps us determine and differentiate various sections of the tune.

Whenever Busta Rhymes comes in for his verse, we hear a tingling, sustained pad, and this is received in stereo. Some delay throws and well-placed effects also hit in stereo, giving us some tantalizing relief. This mix is a masterclass in how to use stereo economically.

2. American Terrorist

Artist: Lupe Fiasco feat. Matthew Santos

Mixing: Craig Bauer

Mastering: Chris Gehringer

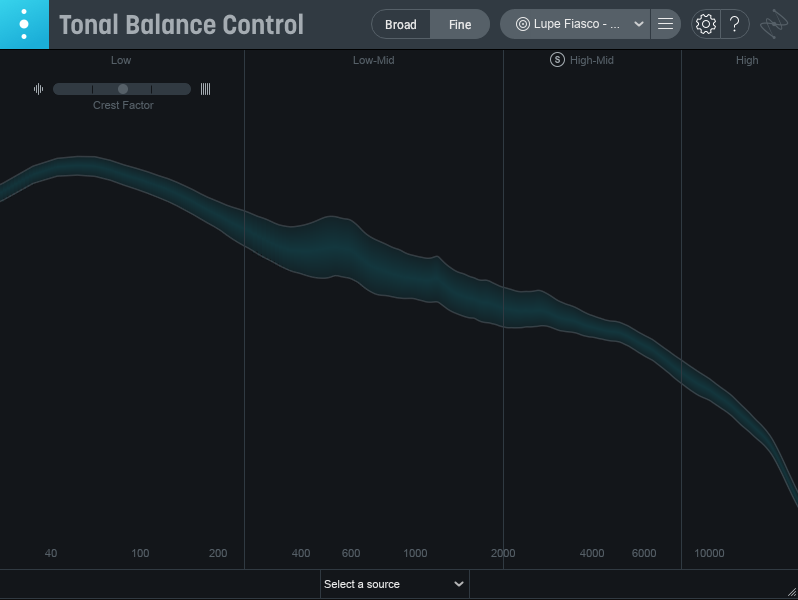

Tonal Balance Control curve for “American Terrorist”

This is one of my favorite records, and so many of the tunes are worth using as reference tracks. However, this is the song I come back to when I’m working on a certain kind of sample-based hip-hop track, both for its sheer energy, and for its aplomb in handling its many elements.

It exhibits a wider stereo spread than the previous tune, with bits of percussion cascading from the left to the right without thwarting our balance. Indeed, contrasted with "Do It Now," the stereo spread is quite apparent, even in the meter:

Stereo field of "American Terrorist"

The kick bumps loudly, without necessitating any extraneous midrange bumps to help it poke through; in hip-hop, kick-click can often get in the way of vocal intelligibility, and this tune provides an example of making a kick like this both heard and felt without detracting from the vocal.

Finally, note how clearly the vocals sit in their own range: between 400 and 600 kHz. You’ll notice that in many of these references, the meat of the vocals is clearly visible in the Tonal Balance Control curves. When you’re mixing your own tracks in comparison, you should hope to achieve a similar response from the vocals in the midrange.

3. King’s Dead

Artist: Jay Rock, Kendrick Lamar, Future, James Blake

Mixing: Matt Schaeffer

Mastering: Mike Bozzi

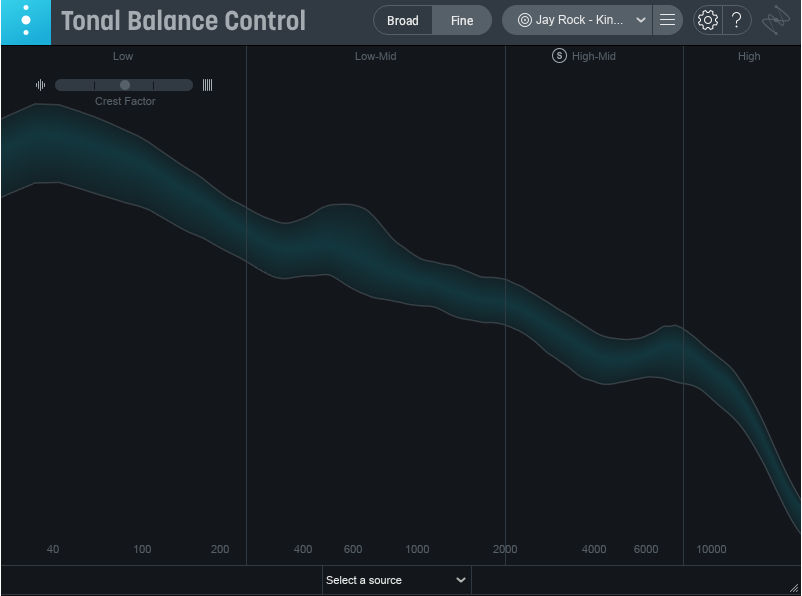

Tonal Balance Control curve for “King’s Dead”

This tune from the Black Panther soundtrack has become a favorite for referencing. One reason to check it out is for its kick drums: there are a few patterns, often in competition with each other, yet we can hear all of them. When using my ears, flipping from my mix to the reference mix, I ask myself if my kick drums are handling their job with the same grace and gravitas.

Also, you’ll note the bass—dirty, out front, growling, but counterbalanced by relatively clean (as in, distortion-free) percussive elements. We’ve got acoustic drum samples in various parts of the sound stage—some in the background, some in the foreground—and yet, they don’t saturate; saturation is left to the bass, and to the reverberated vocal throws.

Analyzing the Tonal Balance Control curve tells us where the vocals tend to sit (around 500 Hz). We can also see where the engineer has attenuated frequencies to fight against harshness (around 4.5 kHz), and where he decided to apply a boost for propulsion and power (around 8 kHz). If my track operated with the same vibe, I may reference these frequency targets, though I’d view them more as a range than a hard target since everything is relative.

I also reference this track for its transition from one marked section to another. For the last five years, hip-hop tracks have often changed in tempo and feel right in the middle of the song. It’s almost as if another song has been injected into the track.

This song uses a stereoized riser followed by strange flanging on the retro instruments, which takes us into a fractured, faster groove, one where the bass is reminiscent of the opening, but nonetheless manipulated into something even more distorted.

The vocals are perfectly played against this differing beat. You’ll also note, if you run this song through its own Tonal Balance Control curve, that the crest factor goes more to the compressed side during this section, which makes sense: we have bass elements cutting through more quickly, and they have been compressed to retain their punch.

4. King Kunta

Artist: Kendrick Lamar

Mixing: Derek “Mixed by Ali” Ali

Mastering: Mike Bozzi

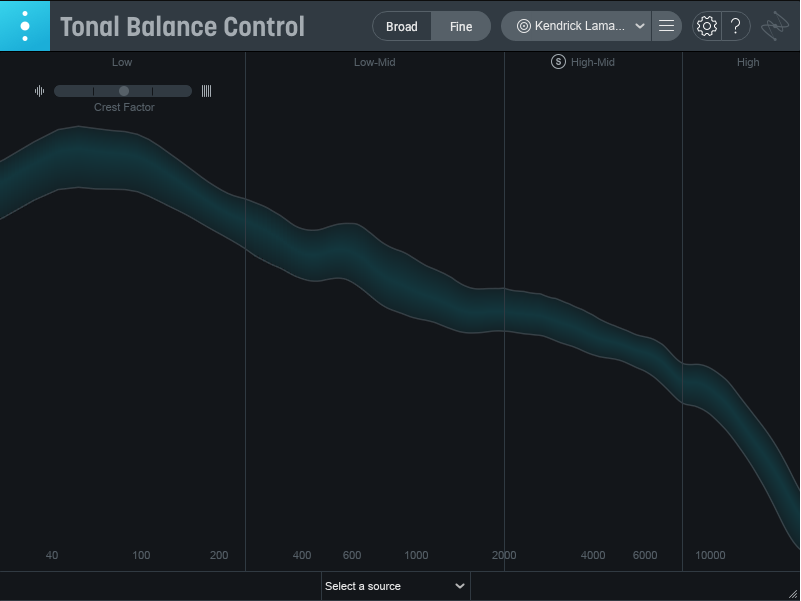

Tonal Balance Control curve for “King Kunta”

This is another track with Kendrick all over it, but the style couldn’t be more different. Whereas “King’s Dead” is arguably more mainstream, this one gives us a more experimental soundbed, as well as a completely different mixing style.

The drums, for instance, take a backseat to a rounded bass. Apart from the vocal, the bass is our standout instrument, though it lacks that midrange cut engineers often employ to make basses growl across laptops.

The Tonal Balance Control curve tells us how well the bass has been contained. It shows us the location of Kendrick’s vocals in visible, elevated ranges. In fact, there’s an overall dip just before Kendrick’s vocal range, around 400 Hz, suggesting great care was taken in given Kendrick’s vocal space.

Also, note the timbre of these vocals: doubled, distorted, and processed, but never widened. Kendrick sits in the middle, no matter the modulation used to harshen his voice. This differs from “King’s Dead,” where one vocal raps up the middle and is reflected back in widened, reverberated throws. Doubled rap vocals are often widened a little, but this mix shows that they don’t have to be.

Finally, we have intricate harmonic instrumentation, with elements introducing themselves throughout the mix. This is a dynamic arrangement indeed. The handling of these elements is worth your scrutiny, for if you have a complicated arrangement—one that consistently stacks from verse to verse—this makes for a good reference.

5. I Like It

Artist: Cardi B feat Bad Bunny, J Balvin

Mixing: Leslie Braithwaite

Mastering: Colin Leonard

Tonal Balance Control curve for “I Like It”

I load up this reference because the majority of the vocals are handled by Cardi B, which I note for the typical difference in frequency ranges between female and male emcees. It certainly isn’t the rule, but a female emcee will often exhibit a core frequency range that sits higher.

In terms of balance, this can change a good deal—perhaps the bass can be situated into the midrange more than it could otherwise. However, there may also be different conflicts between the vocal and snare.

This is a mix I pull up when thinking about these issues. The vocals sit perfectly in contrast to the bass and drums, offering sparkling trebles without any stringent harshness. Also, note the surrounding instruments: the kick, bass, and low-midrange elements all extend a bit in how they’re balanced with the vocals.

There is, however, a limit to their balancing act midway through the tune: a man begins singing, and the elements must accommodate him. The balancing act is part of why I have selected this as a reference.

If we run the song through its own Tonal Balance Control curve, we can see a slight bump just after 4 kHz when Cardi B is rapping, followed by a dip around 6 kHz). This bump and dip smoothen out when the male vocals enter.

All of this tells us where the honeyed sweet-spot is in our female voice (around 4 kHz), and where we need to dip when things get harsh (around 6 kHz).

6. KOD

Artist: J. Cole

Mixing: Juro Davis

Mastering: Chris Athens

Tonal Balance Control for “KOD”

Folks, this mix is clean. No undue grit here. To be sure, all the elements we’ve come to expect are present. The bass is loud and cuts on laptops. The percussion is relatively sparse, and the harmonic elements make room for the vocals, both in terms of arrangement and mix treatment.

However, all of these elements have a clarity that is different from the other mixes we’ve covered thus far. That low bass doesn’t distort nearly as hard as others in this list, staying firmly around 40 and 200 Hz. Our transients are clear and precise: if you solo the Tonal Balance Control ranges, you won’t hear our hi-hat and bell-like elements until the high-midrange. None of these drums sound as though they’ve been fed through a series of saturation plug-ins.

The main vocals are strong, undoubled, sent through the middle. They are full yet clear, not distorted. The reverbs are equally clear, and all of the background vocals wedge pleasantly into the sides of the mix.

If you’re given the imperative to stay clean and modern, yet full and hefty, this is the mix to reference.

7. Nobody Speak

Artist: DJ Shadow Feat. Run the Jewels

Mixing: DJ Shadow, Mikael “Count” Eldridge

Mastering: Bob Macc

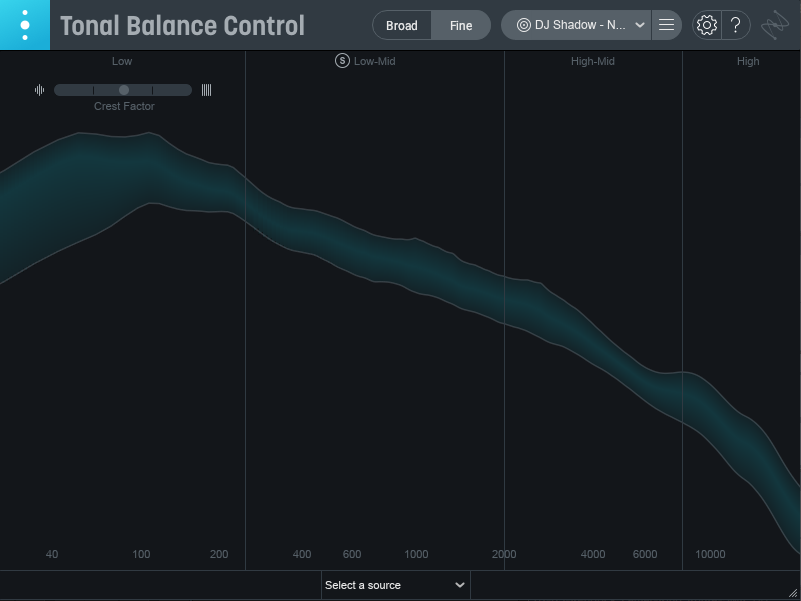

Tonal Balance Control curve for “Nobody Speak”

I mean come on, how could you not love this song? If you want to hear a masterclass on emphasizing a sample while making the mix your own, this is the tune.

“Nobody Speak” samples an arrangement of “Ol’ Man River” from 1968, but uses the sample along with added horns, chords, and arpeggiations from other sources to achieve a completely different vibe. The treatment of sound effects, their levels and blend, is to be commended: if your mix has similar elements, definitely use this as a reference.

The Tonal Balance Control curve shows off the mix’s balance: we see bumps around 50 Hz, 110 Hz, 220 Hz, 1 kHz, 2.5 kHz, and 9 kHz, and these respond to individual instruments: Kick, bass, guitars, vocals, brass, and hi-hats. Each element is perfectly delineated, perfectly balanced.

8. Darkness

Artist: Eminem

Mixing: N/A

Mastering: N/A

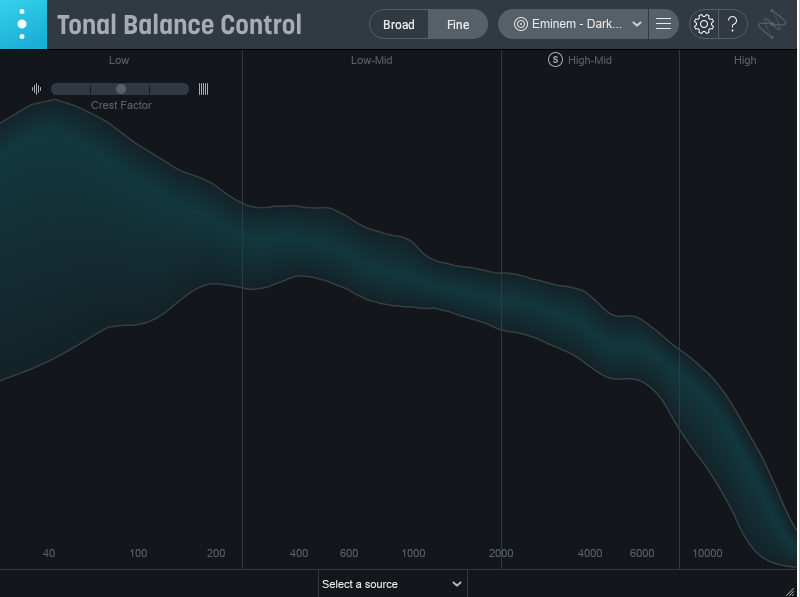

Tonal Balance Control curve for “Darkness”

This is a relatively new track, one that samples Paul Simon. “Darkness” takes some of the most prevalent elements from 2010s hip-hop into a new decade: we’re still bass-heavy—with growling treatment on the low end—but not overblown. We have reverbs, but they’re not nearly as bleary and wet as they were a couple years ago.

What I like about this mix as a reference is the treatment of the bass—particularly, the way distortion was employed to help the bass instrument cut through on laptop speakers. It’s audible and it does its job, but it doesn’t overwhelm the low-midrange on a full range system.

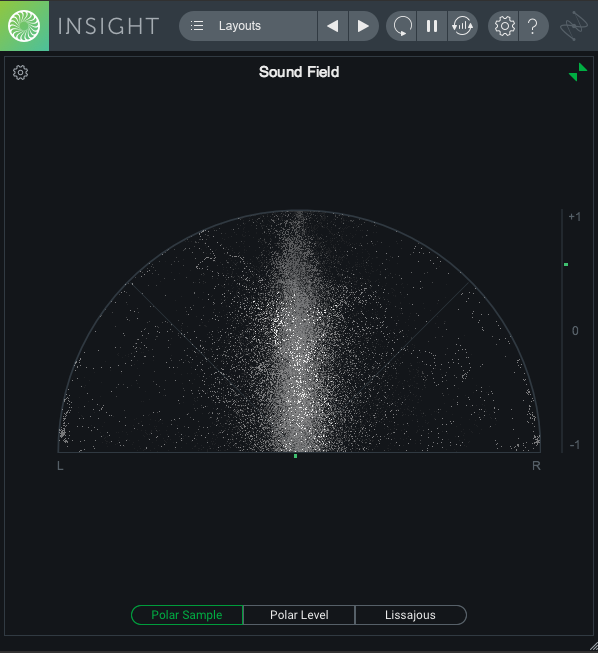

This track is also a primer on handling stereo drums for an experience that doesn’t feel phasey in mono, but is quite interesting on headphones. When we analyze the stereo spread in the meters, we see that it’s sometimes quite wide:

Stereo field for "Darkness"

If you’re trying to do something interesting with a stereo effect, the ancillary drums that skip their way in and out of the tune are worth referencing.

Conclusion

Doubtlessly there are more songs for us to examine, but these tunes offer an excellent starting point. Use them as you wish, but don’t stop with just these! Reference mixes are inherently personal. Listen to these and judge for yourself whether they speak to you. If not, I hope this article piqued your thoughts in a different way, and that I’ve given you a taste of what to look for when fishing for your own references as well. If that’s the case, we wish you happy hunting!